Exercise for the Human Knee

Part IV

by Ken Hutchins

Note: This material is excerpted from a more-complete chapter in

The Renaissance of Exercise—Volume II (ROE-II) by Ken Hutchins.

In Part I of this series, I described the general anatomy and mechanics about the knee. Then I explained transposition between rotary-form and linear-form motion that occurs both within the body and within the mechanics of an exercise machine. I culminated this presentation with the idea of transpositional shift. Therein, I made no allusions to the mechanical couple or the coupled movement arm.

In Part II, I explained that a rotary-form exercise machine allows rotary-form joint movement but might not impose rotation at the joint. Then I clearly described the meaning of the gobbledygook often spouted as closed-chain or open-chain exercise and its related shear force nonsense. In the course of explaining and condemning these ideas, I provided graphics and discussion regarding the changing reactionary forces at play in various exercises. I did briefly allude to the coupled movement arm.

In Part III, I provided (March 2013) the resistance curves of several of the older Nautilus Leg Extension machines as well as curves and/or commentary regarding Cybex®/Eagle®, MedX®, SuperSlow®, David®, and RenEx®. I did this to show the often-overlooked external variances of load placed on the knee by different knee extension devices. I used this information to present my personal rankings of these products regarding shear threat to the knee. I completed with the suggestion that the coupled movement arm is the solution to many—albeit perhaps irrational—fears regarding knee exercise.

Now, for the first time, I present detailed analysis of the coupled movement arm.

The Coupled Movement Arm

If the shear talkers insist on their supposed dangers regarding knee extension exercise (especially during the last 15-30 degrees of extension), the coupled movement arm is the probable cure to their nightmares. Of course, one of the many problems with nightmares is that they are often not reality. However, such irrational fear often permanently prejudices the mind to consider reasonable outcomes and beneficial solutions.

A quick definition of the mechanical couple found on-line is:

… a system of forces with a resultant (a.k.a. net, or sum) moment but no resultant force. Another term for a couple is a pure moment. Its effect is to create rotation without translation, or more generally without any acceleration of the centre of mass.

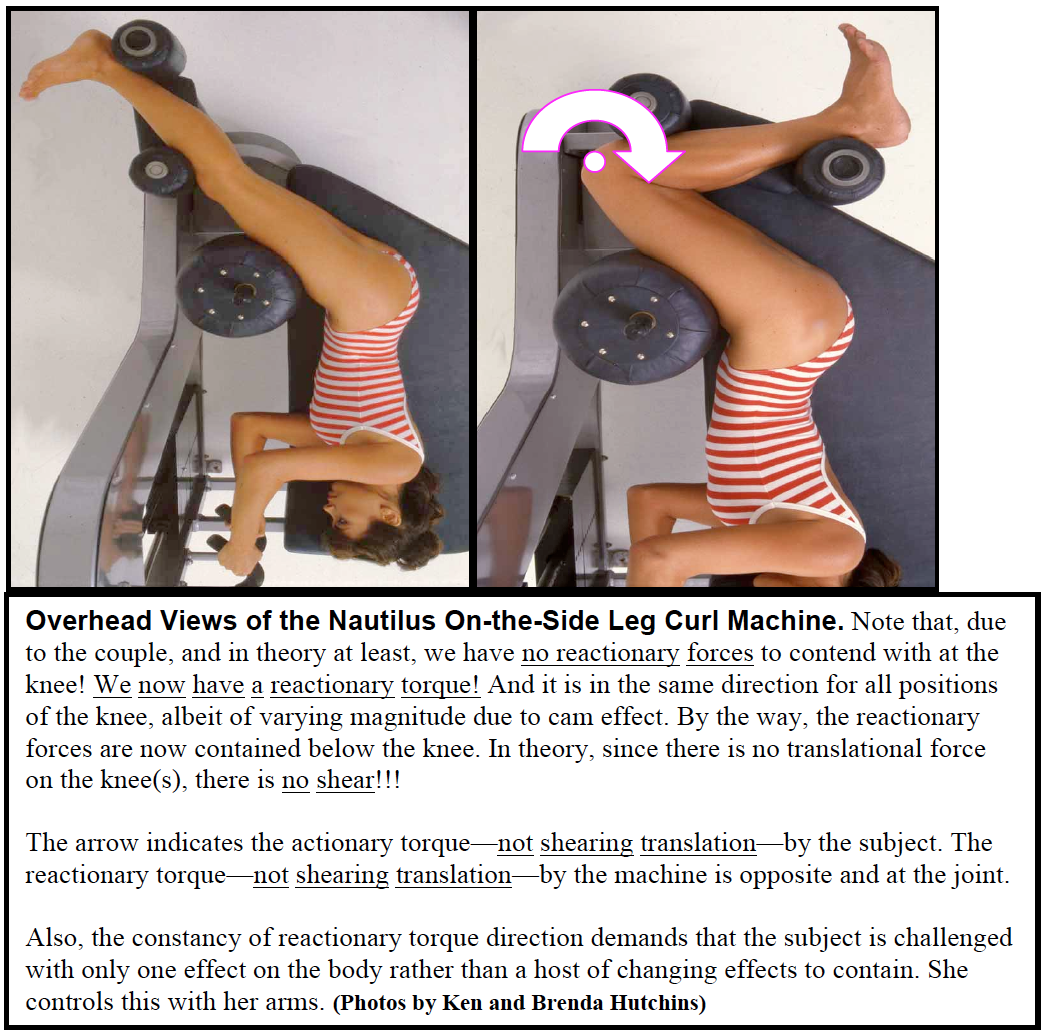

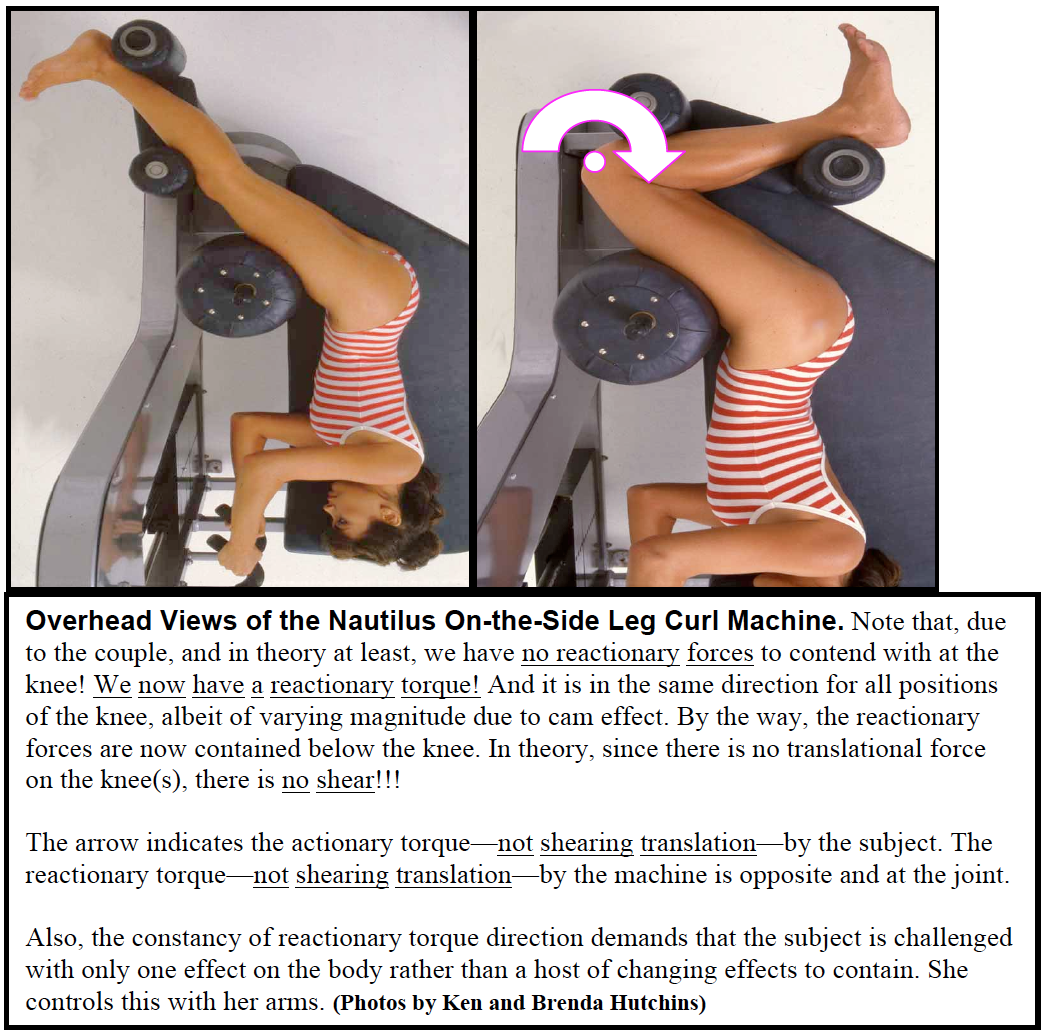

For example, the coupled movement arm in a knee flexion machine applies two pads at indirectly opposing positions, distal to the knee. Equal and opposite forces, indirectly applied, allow rotation at only the knee—theoretically. Also note that the reactionary torque—not force—on the proximal bone—the femur in this case—is always in the same direction. This constant reactionary tendency is always about the knee with the opposite and equal torque as the movement-arm torque.

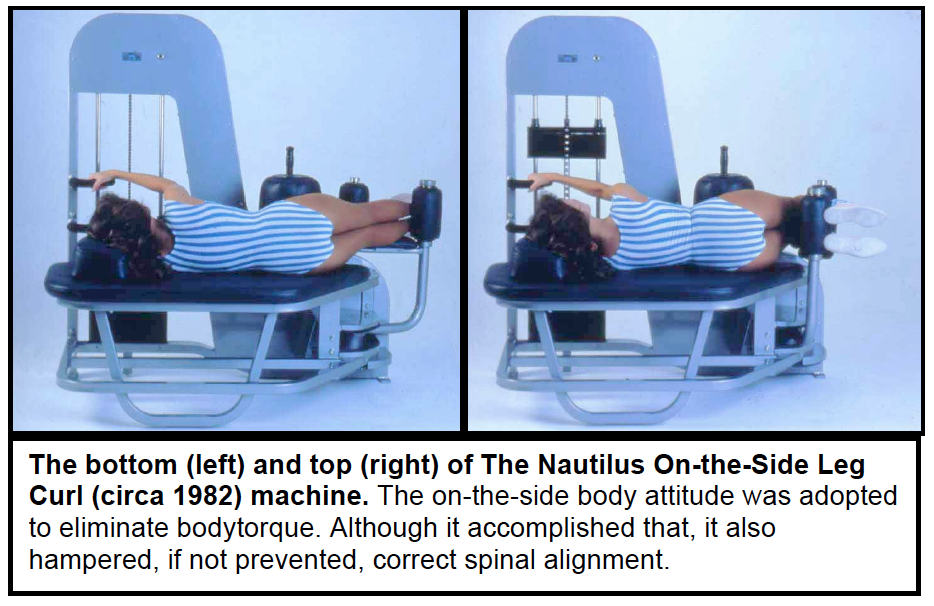

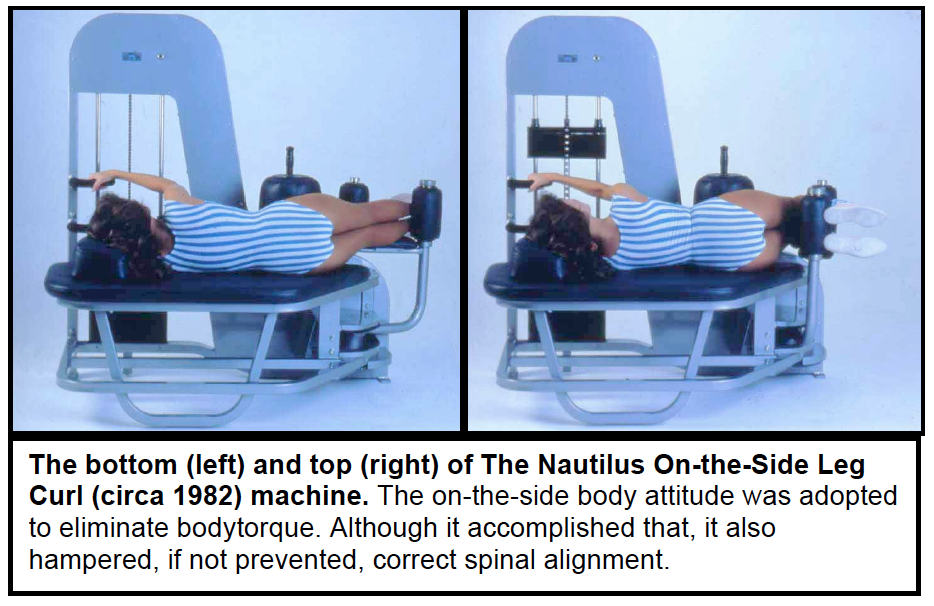

The first Nautilus product to emerge with a coupled movement arm was the On-the-Side Leg Curl (knee flexion). Shortly afterward, it was Keith Johnson’s (MD) idea to rotate the subject’s body attitude into a seated position and make the first Nautilus Seated Leg Curl (knee flexion) incorporating the same coupled movement arm that was first found in the On-the-Side machine.

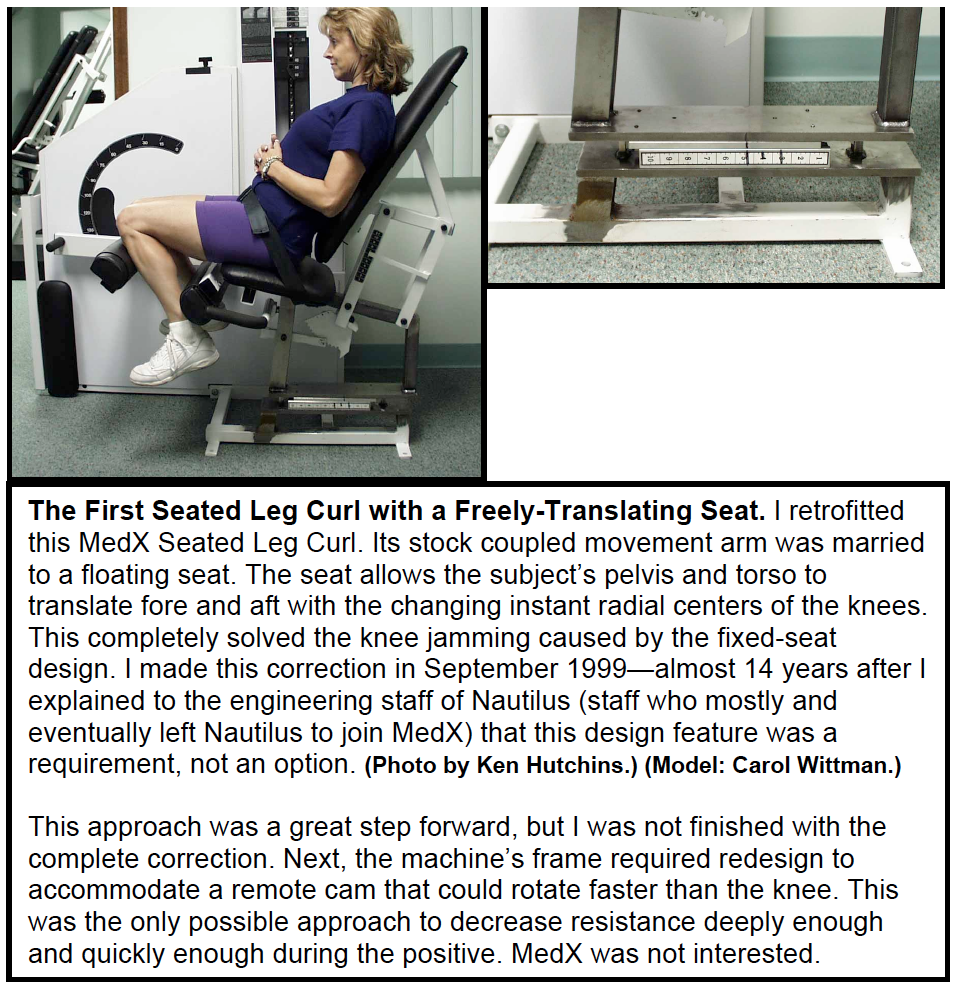

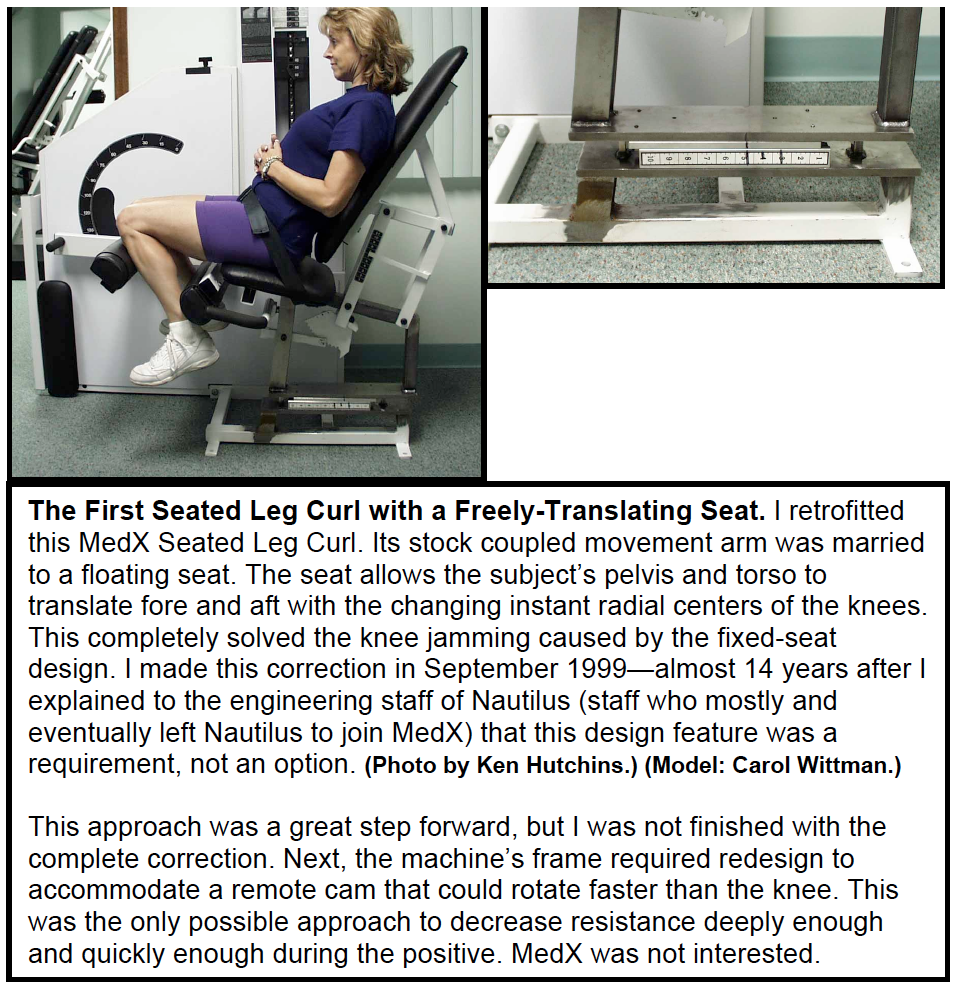

I, alone, championed Keith’s idea at Nautilus. After trying for nearly two years to get Arthur to consider Keith’s idea, I convinced George Johns to build one in the Nautilus prototype shop. I then explained its requirement for a floating seat, but George postponed this indefinitely saying that perhaps a deluxe version incorporating a moving seat could be considered later.

Nevertheless, when Arthur first saw the prototype—fixed seat—and asked George to demonstrate it, Arthur exclaimed that it was the most important new product the company had developed in years. And, as I later learned, this was a critical moment for Arthur as he was trying to make the company appear to have a future of growth and innovation so that he could sell it. The date was late May of 1986.

Ellington Darden overheard Arthur’s excitement and mentioned that, “Ken Hutchins has been trying to get someone to build this for two years,” Arthur quipped, “Well, why didn’t he come talk to me about it?!”

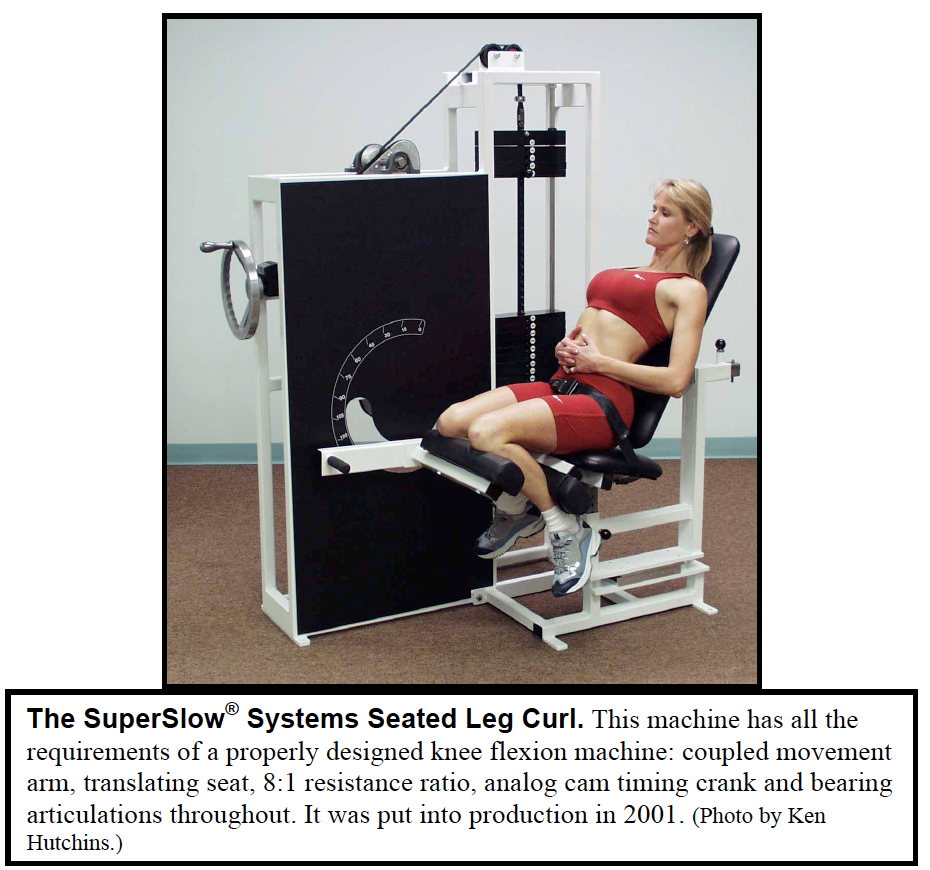

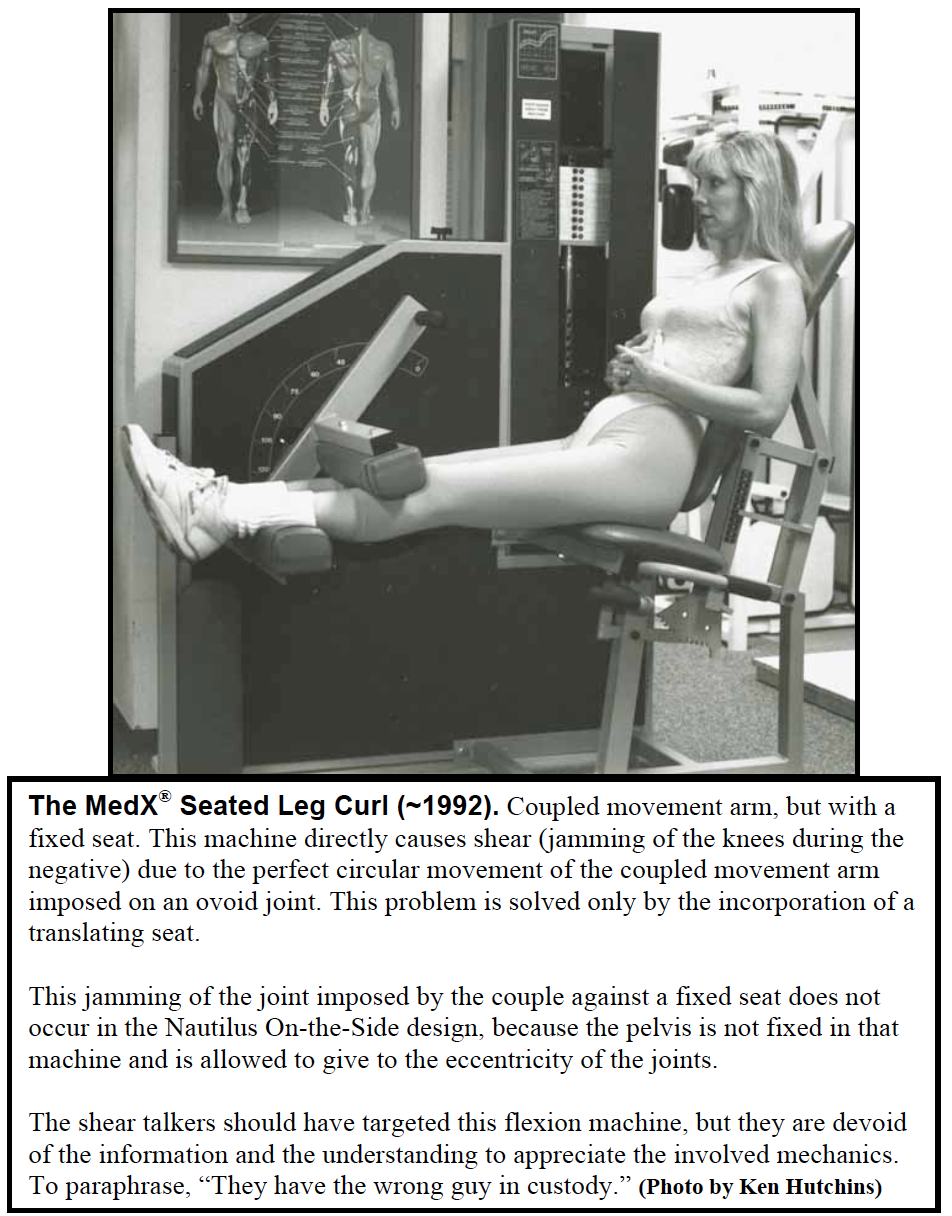

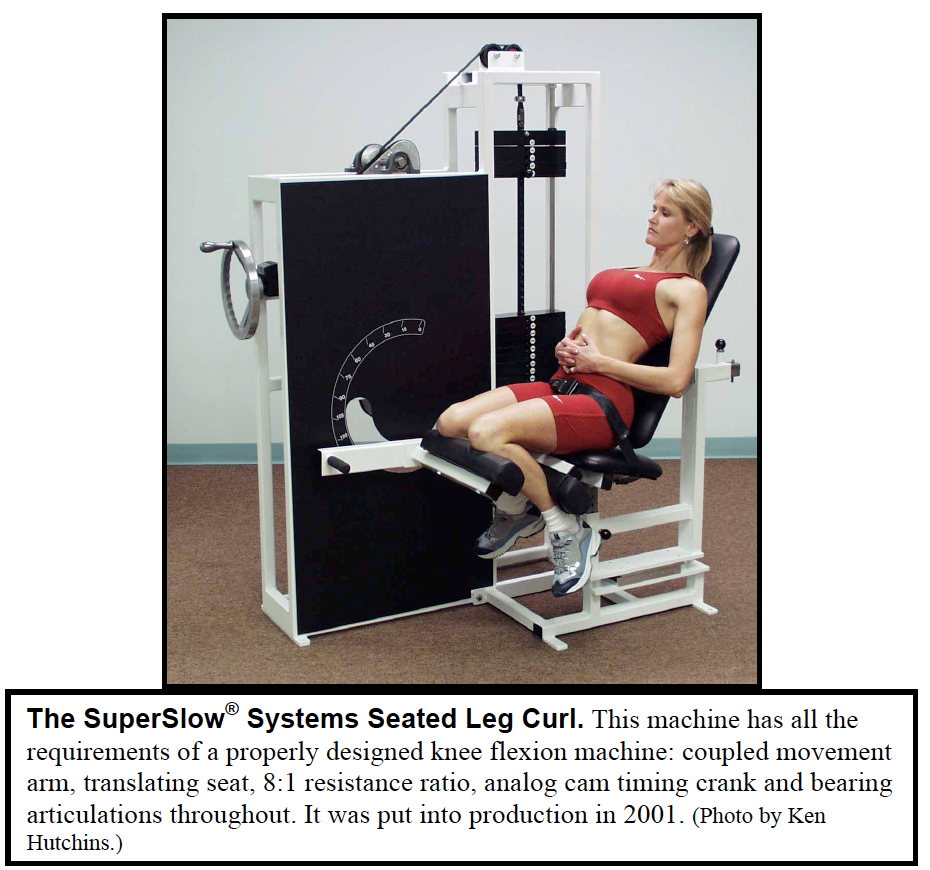

I immediately and consistently railed that this seated knee flexion machine required a freely translating seat, but it did not get one until I made one for SuperSlow® Systems approximately 14 years after my protest began.

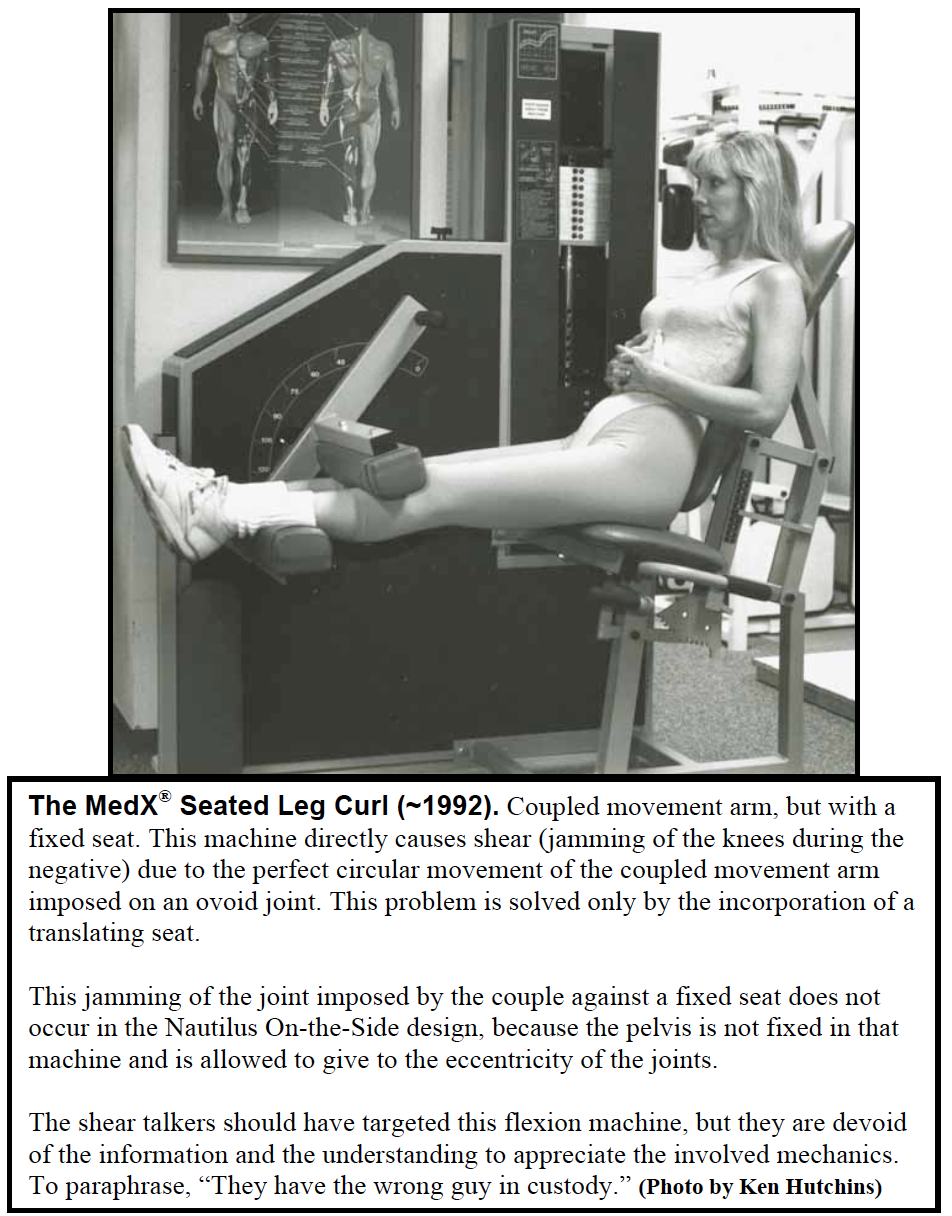

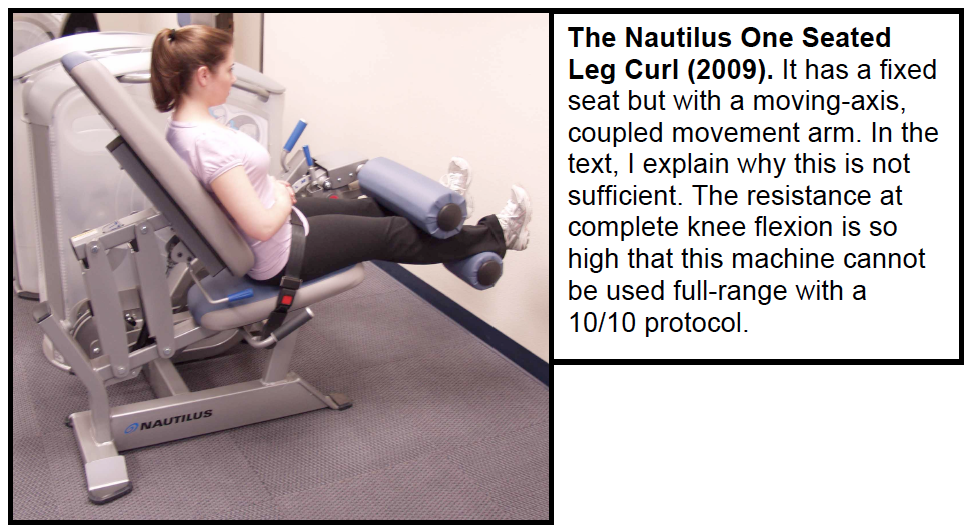

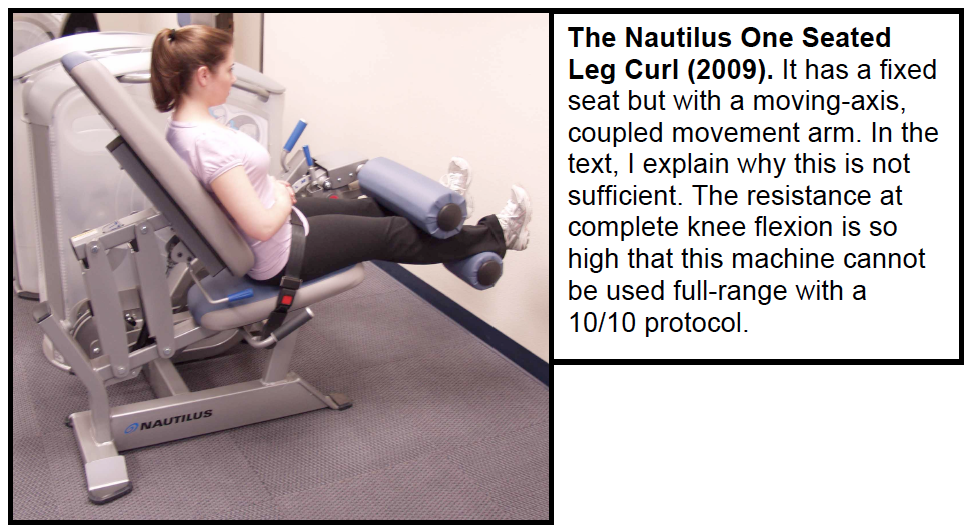

Regardless of my proclamations about the requirement for a translating seat, Nautilus and MedX marketed fixed-seat versions of seated/coupled-movement-arm knee flexion machines. The latest Nautilus incarnation is the Nautilus One that purports to cure the problem with its floating-axis movement arm, although the seat is fixed. Sorry, this doesn’t go far enough.

With the Nautilus One, the translation range of its axis is arbitrarily fixed which might be perfect for some subjects, too much for others, and inadequate for a third group. And these categories are inter-dependent upon the seat back being expertly and unlikely placed at a distance particular to the subject’s thigh length. Load, pad compression, flesh compression, and bone bending figure into this as well.

Ken’s dictum: The seat must freely translate! Nothing short of this is acceptable!

Now note that to “freely translate” the seat’s range must not delimit the largest possible translational range of any subject’s knee eccentricity. This means that no subject—small or large, normal or abnormal—is going to move fore and aft far enough to abut the ends of the seat’s travel when the seatback is properly set and the leg(s) are properly positioned in the couple of the movement arm.

The On-the-Side Distraction

Both Nautilus and MedX introduced their coupled-movement arm devices with an on-the-side body orientation. At least Nautilus ceased the on-the-side approach. And while MedX almost simultaneously made its fixed-seat Seated Leg Curl, MedX trudged onward with its on-the-side folly by making its version of the On-the-Side Leg Curl and its On-the-Side Abdominal (Hip or “Torso” flexion) machines.

MedX also produced its coupled-movement-arm, On-the-Side Hip&Back (hip extension) machine. It is shown in the middle of this video on YouTube (Starting at 1:54):

(Although with a supine orientation, I made the first-attempt prototype at a coupled-movement-arm Hip&Back machine at Nautilus in late 1986. It worked, but was not practical in the way I left it unfinished.)

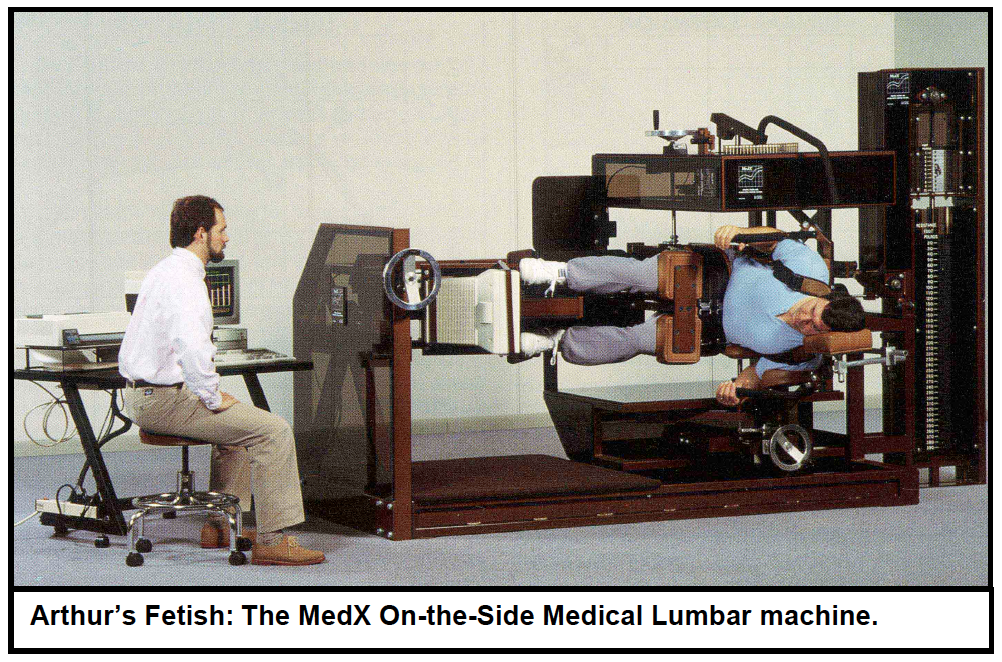

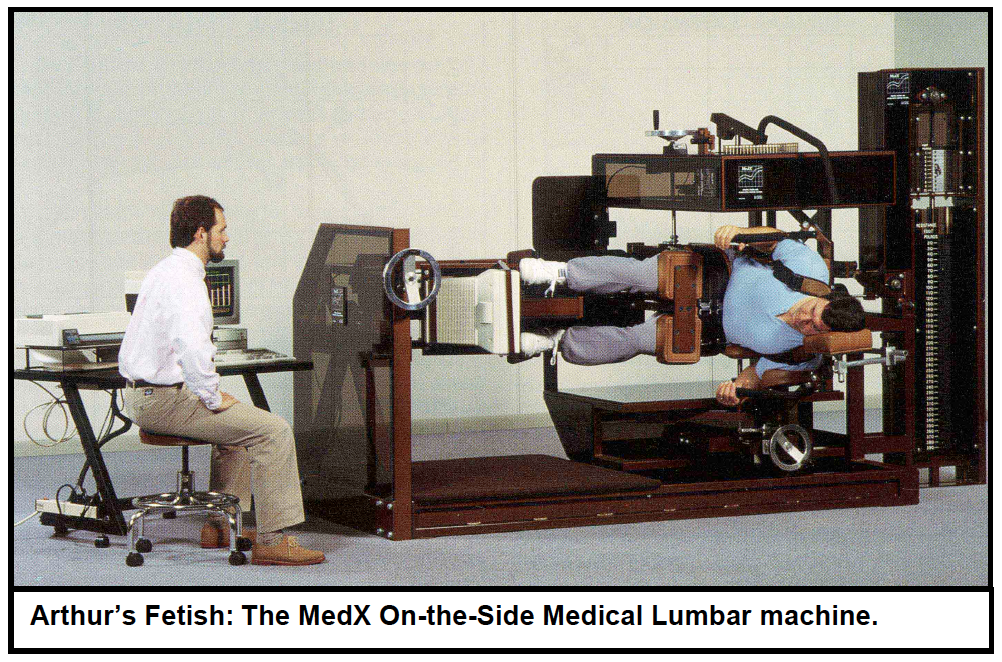

MedX also made an extremely expensive on-the-side Medical Lumbar machine. Arthur Jones justified this monstrosity to eliminate the bodytorque in the exercise as well as in testing. For those readers not aware, bodytorque is the undesirable effect of the body’s mass acting upon the machine’s movement arm. This mass (length, mass, and mass

distribution along the length) produces torque magnitudes that vary against gravity depending upon the position of the body’s mass relative to the axis of rotation. In some exercises where large body parts are involved, this is a serious concern. For smaller limbs—especially the proximal arms and legs—it is of lesser concern, usually negligible.

Rotation about a vertical axis (on-the-side) perfectly solves the bodytorque problem, but it introduces other problems that were not there with a horizontal-axis orientation. It now becomes exceedingly difficult to keep the spine straight. And this criticism includes the head and neck. It also requires that one side of the body support the subject’s weight. And this often causes an undesirable, uneven loading on bilateral musculatures.

One aspect of the historical progression from non-coupled-movement-arm to coupled- movement-arm design that still puzzles me is why use the on-the-side attitude for knee flexion in the first place. Yes, I appreciate the bodytorque frustration with the trunk exercises such as Hip&Back, Abdominal, and the Medical Lumbar machines, but Leg Curl?! Unless dealing with a very specific need to address a very debilitated patent, lower-leg bodytorque is not worth the effort—at least not for the general population. And I as alluded before, Nautilus wisely dropped the approach, while MedX—I’m sure with Arthur’s out-of-touch steering—continued in this outrageous direction.

Still, why start with an on-the-side coupled-movement-arm Leg Curl in the first place? My hunch is that the Nautilus engineers merely wanted to satisfy Arthur’s penchant for making something—anything—with a vertical axis. This was in 1982. And what we see coming out of MedX a decade later seems to show that Arthur remained hell bent on this penchant.

By the way, although on-the-side machines still remain in the field, they are no longer offered by any manufacturer that I am aware.

More Specifics of the Couple

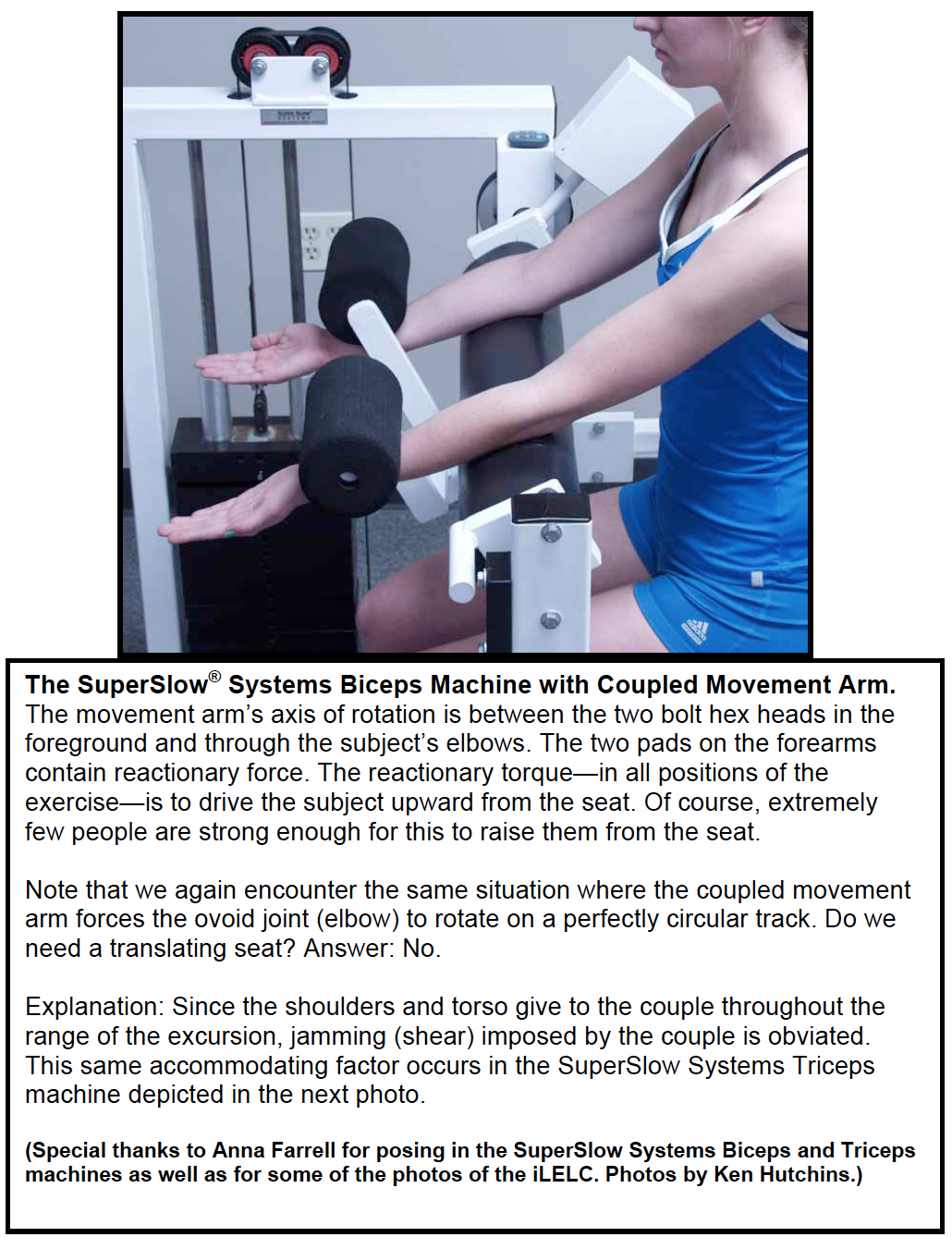

By studying the photographs supplied herein, you can now appreciate several aspects of the couple. As you refer to the picture of the SuperSlow Systems Seated Leg Curl I now repeat some of its already-mentioned details as well as add some new ones for clarity. I number the points:

- Referring to the joint, per se, the coupled movement arm imposes a reactionary torque, (not the variously-directioned reactionary forces discussed and illustrated in Part II of this series) against the actionary torque of the knee.

- All force(s) about the movement arm and legs—actionary and reactionary—is/are contained distally to the knee and cancelled into the lower-leg bones. Therefore, there is no shear at the knee joints.

- The overall reactionary effect upon the subject’s body is to rotate her clockwise regardless of knee position. Therefore, if we consider all of her body that is proximal to the knee as a system, that system experiences a torque in any particular position.

- And since torque is a product of two factors (lever and force), then that product can be factored. The force (in addition to her partial bodyweight) between her buttocks and the seat is a factor of the systemic torque.

- Therefore, application of the coupled movement arm shields all external forces from the knee. Force is either contained below the knee between the two movement-arm pads or factored out of the systemic torque upstream (proximal to the knee).

Note: I have been aware of points #1 and #3 for 29 years. In fact, I have occasionally discussed these points with some advanced instructors as well as other prototypists over the years. And each of these conversations was a one-way conversation. No one has ever told me any of this. I have never read any of this. And none of my engineer contacts at Nautilus or MedX have posited back to me that it was incorrect, or that it was useful information around which to design equipment, or even so much as a “so what?”

My remaining points #2, #4, and #5 are completely new—at least to me.

One last emphasis on the five points: I state that the coupled movement arm renders containment and cancellation of the reactionary forces into the bones distal to the knee joint. This is correct. But do not interpret this to mean that the forces go away. They do not. They are merely grounded—so to speak—into the bones (as well as some of the soft tissue surrounding the bones, especially the calf musculatures). The shear is now on the bones proximal to the knees.

There are conditions where this must be considered. And one of these is the fact that there is a minimal distance that the coupling pads must be arranged from each other. As the proximal and distal couple pads approach closer together, the forces (shear) become exponential! Of course, the knees don’t care about this, but your bones might.

The Coupled-Movement-Arm Knee Machine:

A Dynamic Jig?

An Exoskeletal Joint?

A Loadable Brace?

In theory, a couple-movement arm allows for safe rotation about a knee that has no cruciates, indeed no ligaments at all. The couple protects the joint—in a sense, becomes the joint!

Couple Failure

My five specific points about the couple—of course—are theoretical. But with a properly designed machine, they are also reality. They have immense practical value for many subjects. This reality evaporates, however, with excessive speed, i.e., anything faster than about 8 seconds uniformly performed. Therefore a strict adherence to a 10/10 protocol is mandatory to prevent couple failure.

[Like everything else in the world, technical measurements assume a tolerance. When I stipulate a “strict adherence to a 10/10 protocol,” this is known by the knowledgeable in our field to have a +/- 0.2 tolerance. It has been detailed in every edition of the SuperSlow Technical Manual and the RenEx Textbook (ROE-I).]

When the subject moves just slightly too fast to maintain volitional control the mechanical couple of the movement arm fails. This is almost always the result of excessive speed and/or subscribing to the assumed objective.

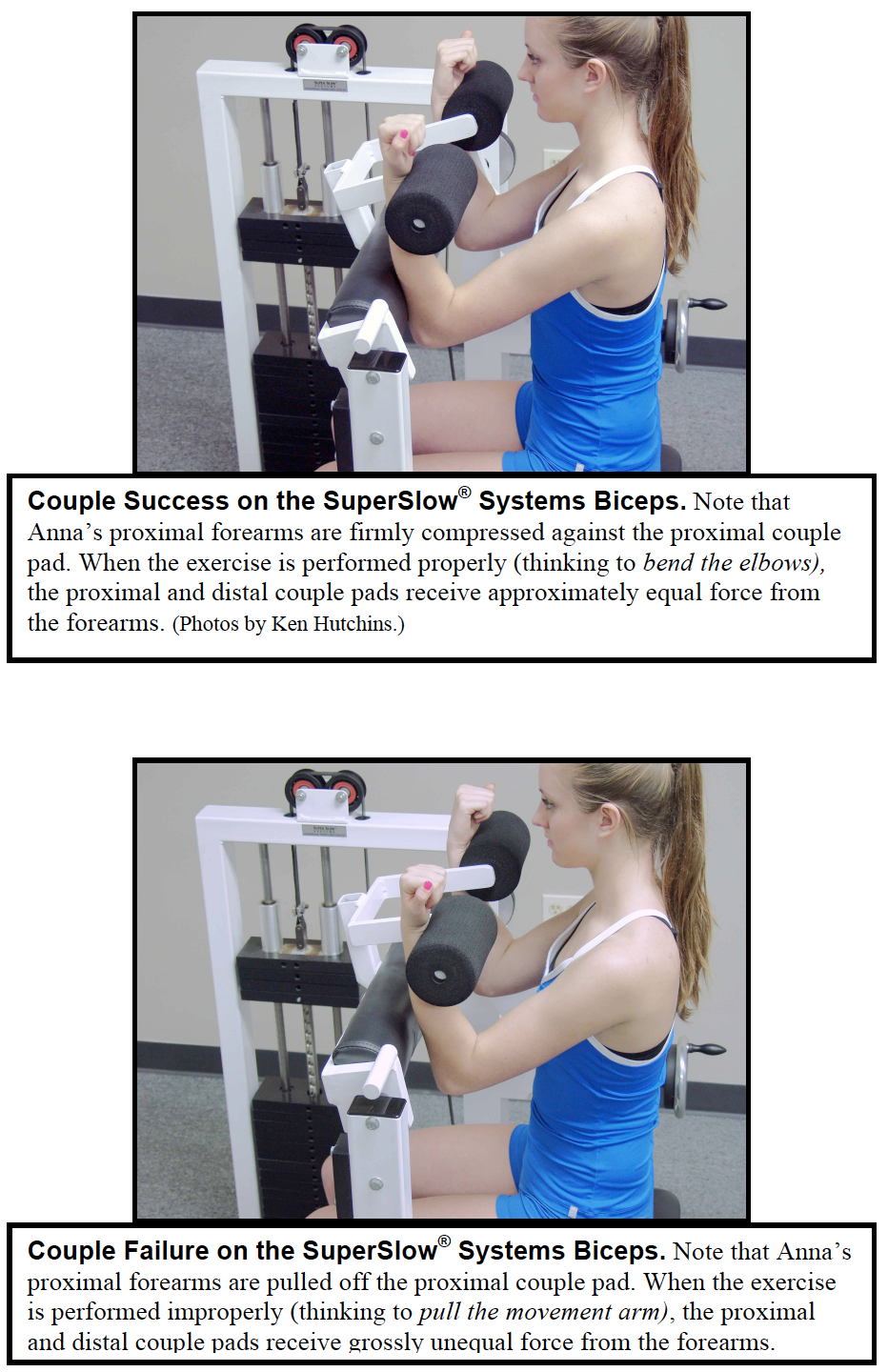

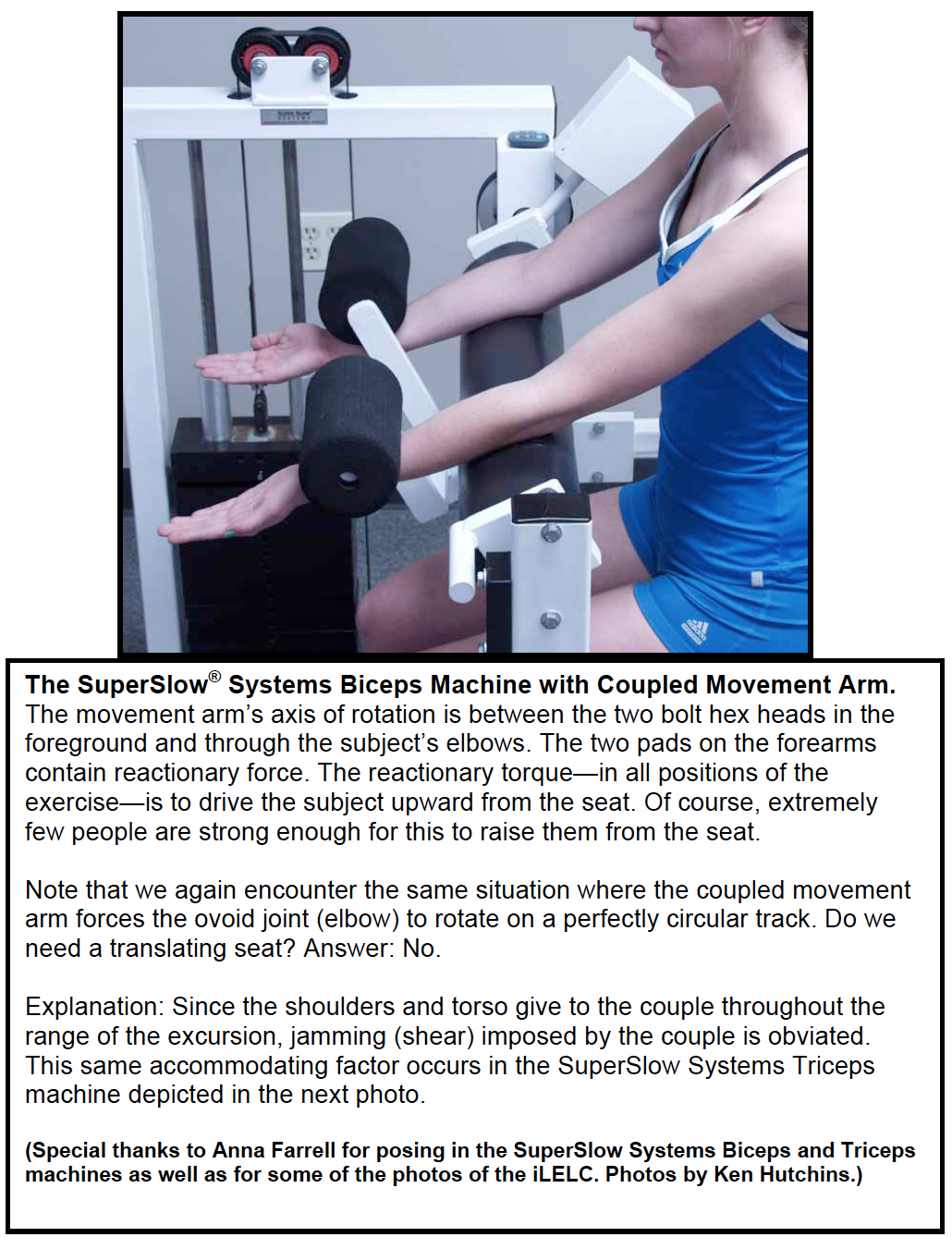

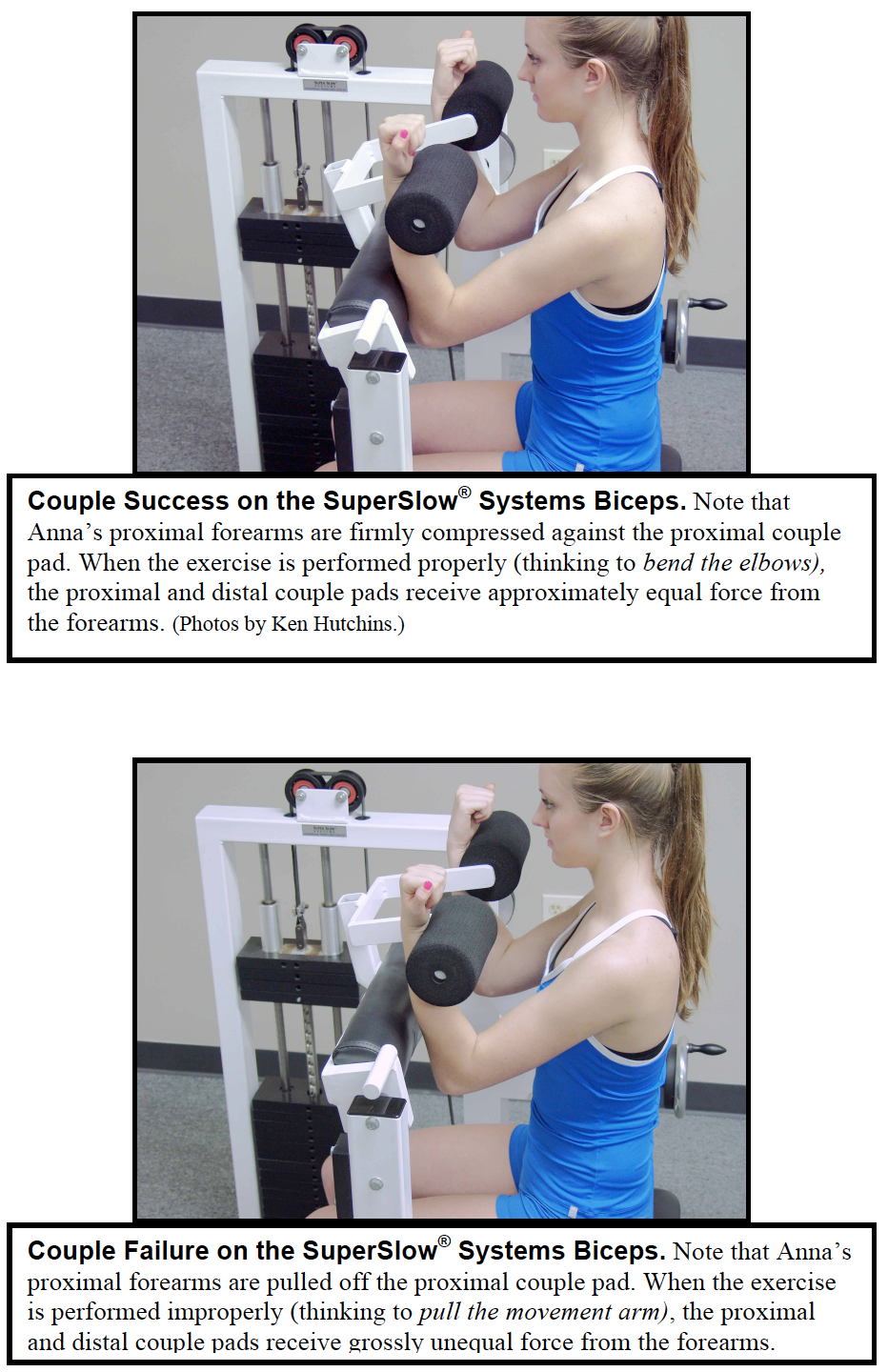

Note the pictures of the SuperSlow Systems Biceps machine above. In the first, the elbows are correctly held against the more-proximal arm pad. In this elbow position near and nearing the top of the positive range, the elbows are likely to leave this proximal pad as depicted in the second photo. This discrepancy occurs literally because the subject has improper thoughts.

The correct behavior does not occur merely because the subject elects to push her elbows forward. The couple, alone, will take care of this. The couple will bring the proximal forearms forward and tight to the proximal pad. But the subject must allow this to occur.

And the subject allows this to properly occur by subscribing to the real objective, by commanding her body to: “Bend my elbows.”

If the subject goes the natural way—subscribing to the assumed objective and commands her body to lift the weights by pulling the movement arm backwards—we have couple failure. Couple failure is evidenced by the proximal forearms leaving the proximal pads.

With such misbehavior we are instantly returned to incurring actionary and reactionary forces (as in a non-coupled movement arm)—instead of an actionary torque against a reactionary torque (as in a coupled movement arm). Fast movement coupled with mindlessness and carelessness uncouples the couple. And with this we lose the attributes of the couple.

In more specific language: Assume the subject has been properly schooled regarding the RenEx protocol as well as the correct execution of the exercise. As soon as she begins to move slightly too fast (~eight seconds or faster), she can no longer certify her avoidance of the assumed objective. Fast speed begets mindlessness and carelessness. Carelessness begets ratcheting and falling through. And falling through begets couple failure.

Note that, seemingly, we might put a seat back on the Biceps machine to blunt any rearward movement of the subject’s torso. Although I will consider this design, I have misgivings about it, because it does not prevent the volition for incorrect behavior. It merely blunts it. The incorrect thought—or worse, the lack of thought—not only remains, it is somewhat encouraged.

Although we will only study the Biceps machine with the regard to couple failure, herein, suffice it to say that such failure is possible in the coupled movement arms for all the other machines incorporating these special movement arms.

Practical Application to Leg Extension Design

Once Nautilus produced a coupled movement arm for a Leg Curl machine, Arthur expressed doubt that such a movement arm had other applications. He explained that the tibia tuberocity was perhaps the toughest area of the body, and that it made the coupled movement arm possible for the Nautilus Leg Curl.

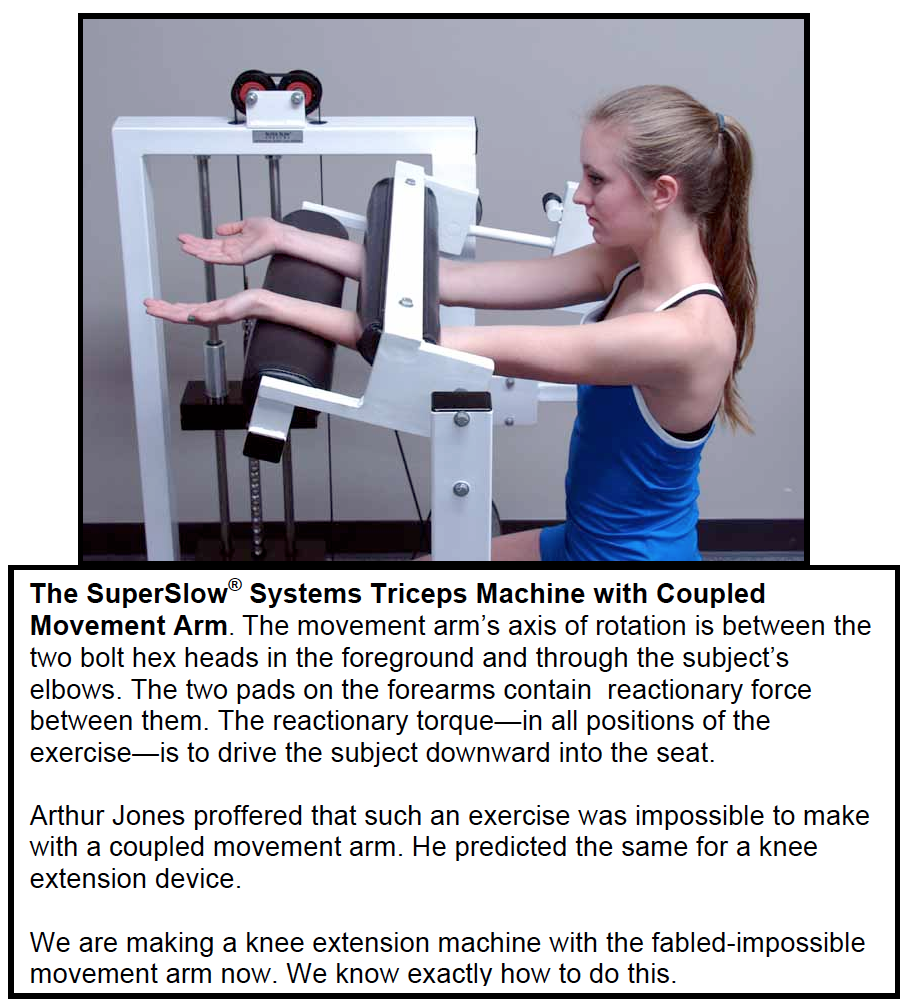

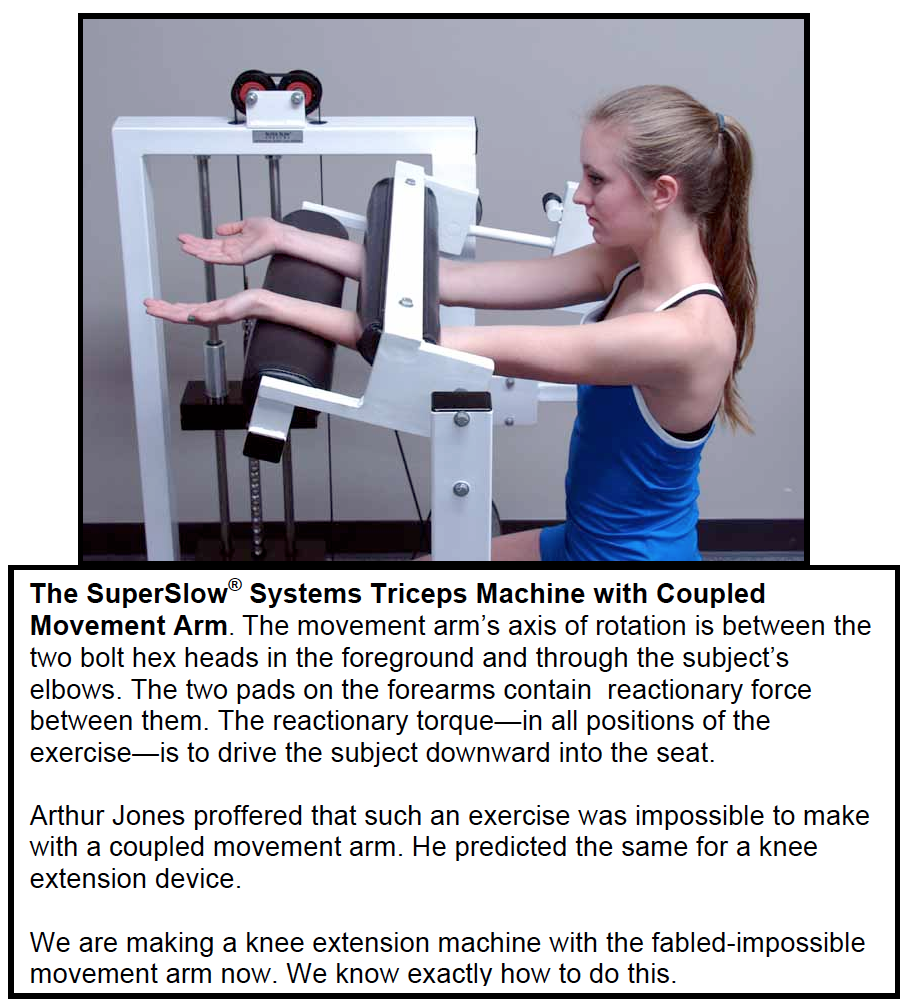

It just did not seem possible for the couple to work when the proximal pad would be needed against the calf as in knee extension, against the pericubitous area of the forearm as in triceps extension or against other like areas. Of course, the olecranon proved worthily robust to apply the couple with the brachial biceps flexion exercise (curl). And then came couples that seemed to defy Arthur’s prediction: Hip&Back (me and MedX), Triceps (SuperSlow Systems).

Several years ago I heard a rumor that someone had made a neck machine with a coupled movement arm. I find this both unlikely and scary. I could never ascertain that the source of this report really understood the definition of a couple.

And to the best of my knowledge, no one else has yet to design a coupled movement arm for knee extension. I have done this, and we at RenEx are presently building it. And once complete, it will be the most perfect knee rehabilitation machine ever developed. However, we already have that distinction with both our dynamic and static devices. Putting a coupled movement arm on the dynamic device will merely jettison our lead in the industry a quantum leap ahead than it already is.

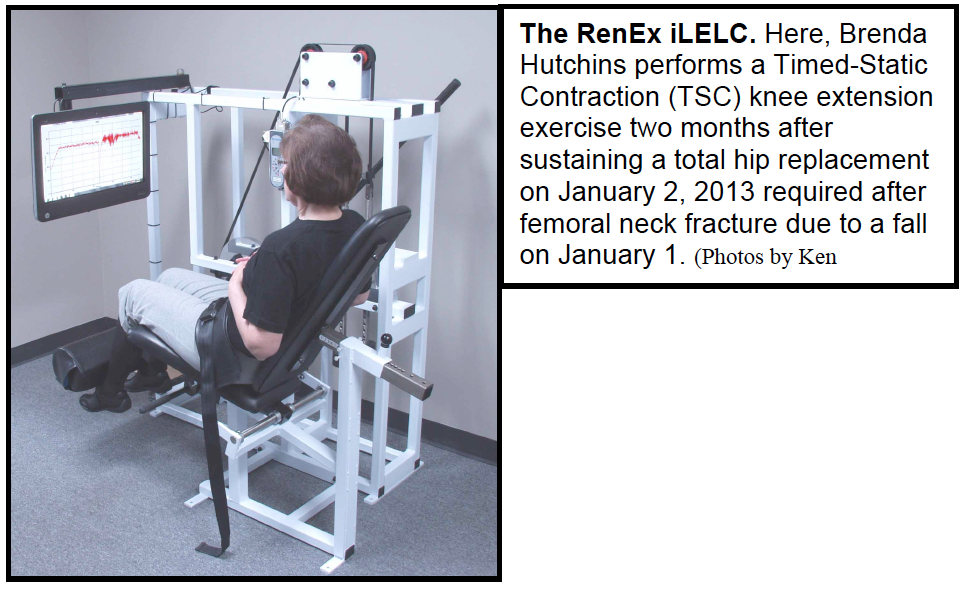

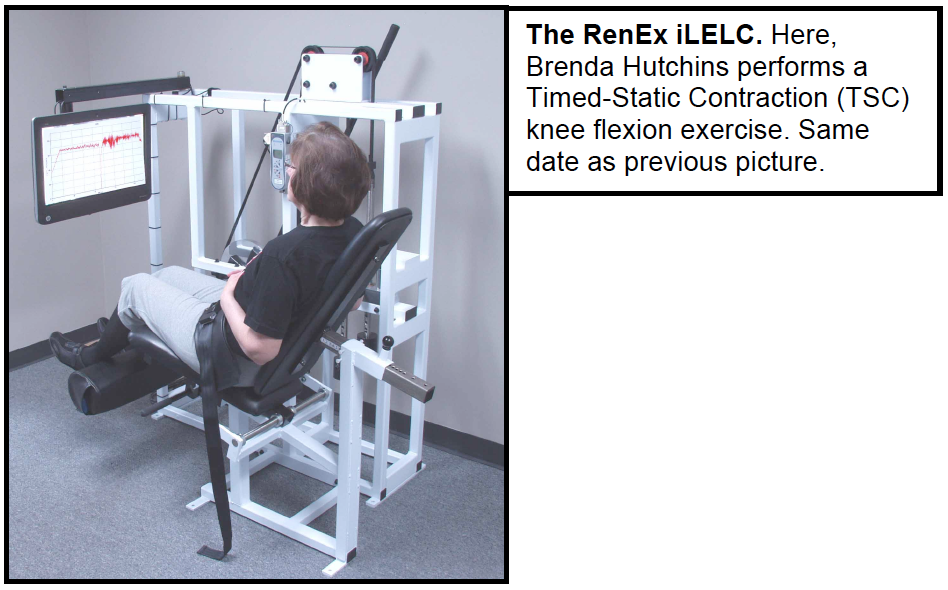

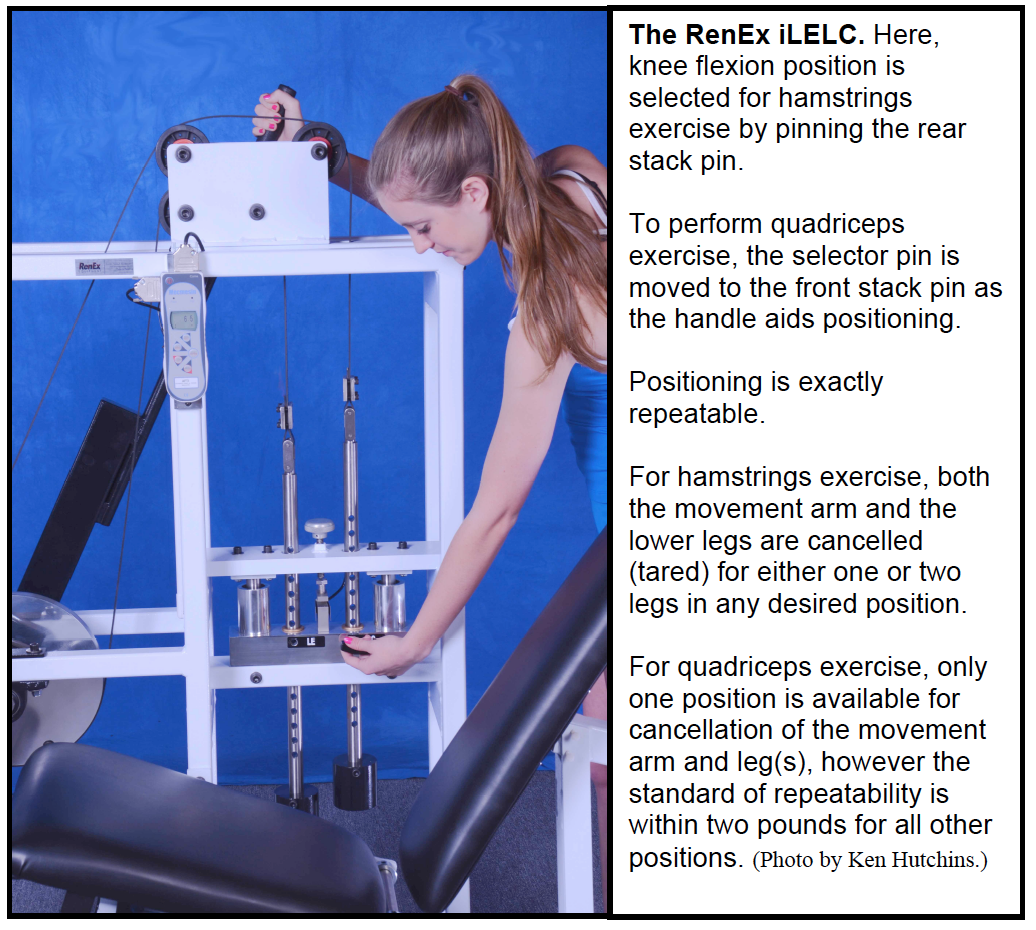

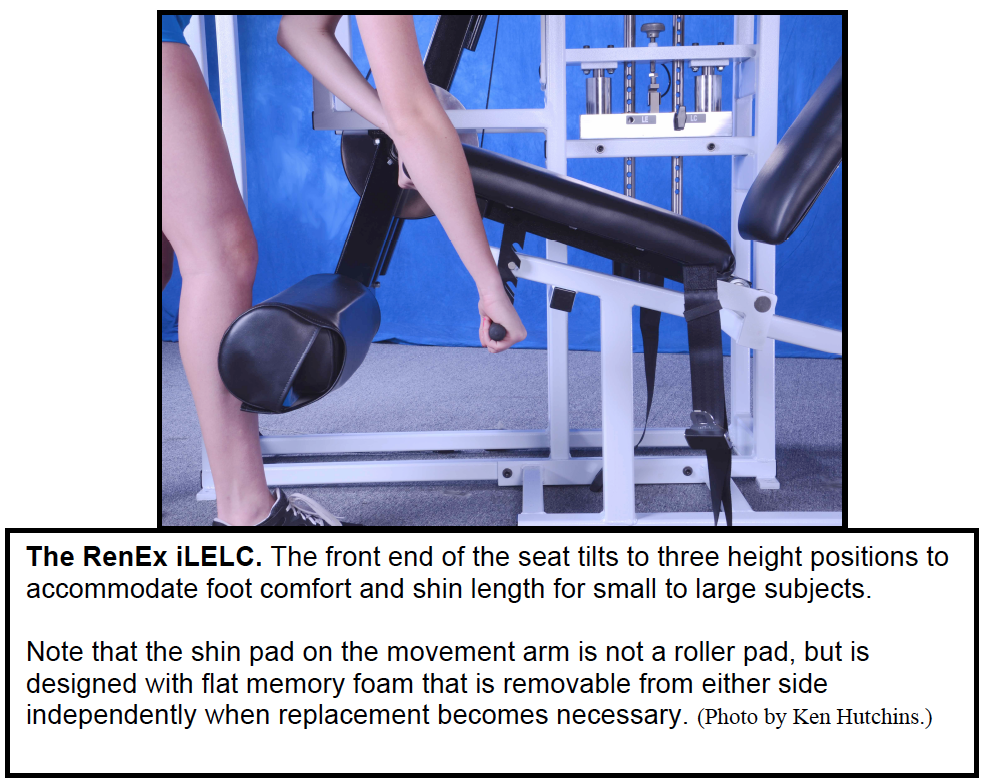

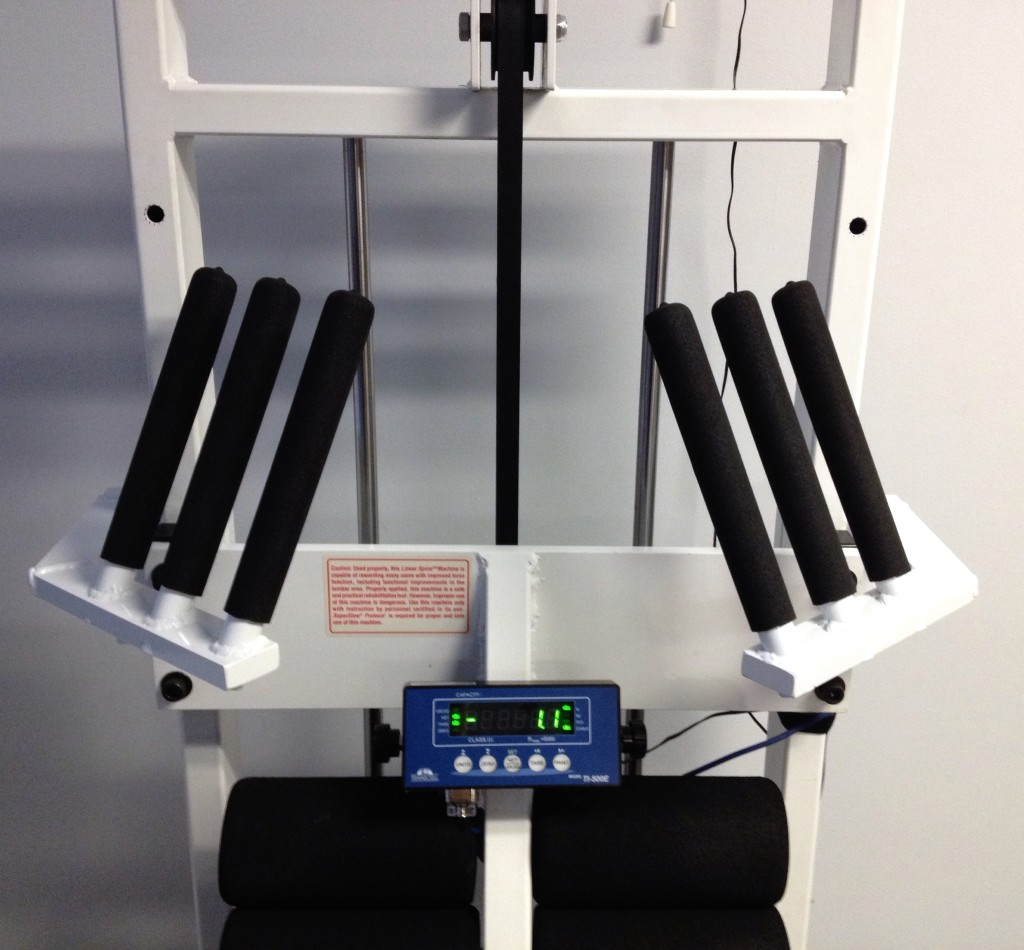

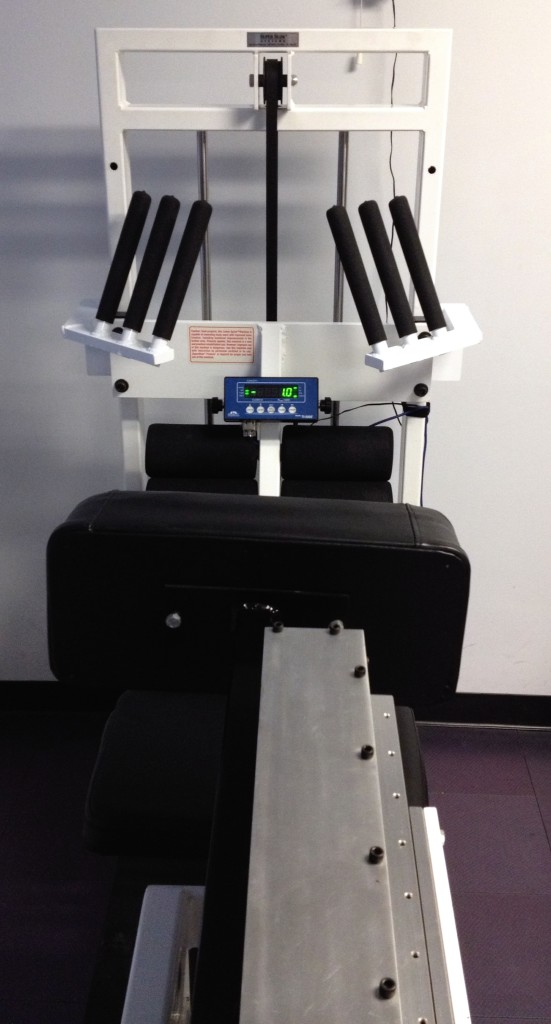

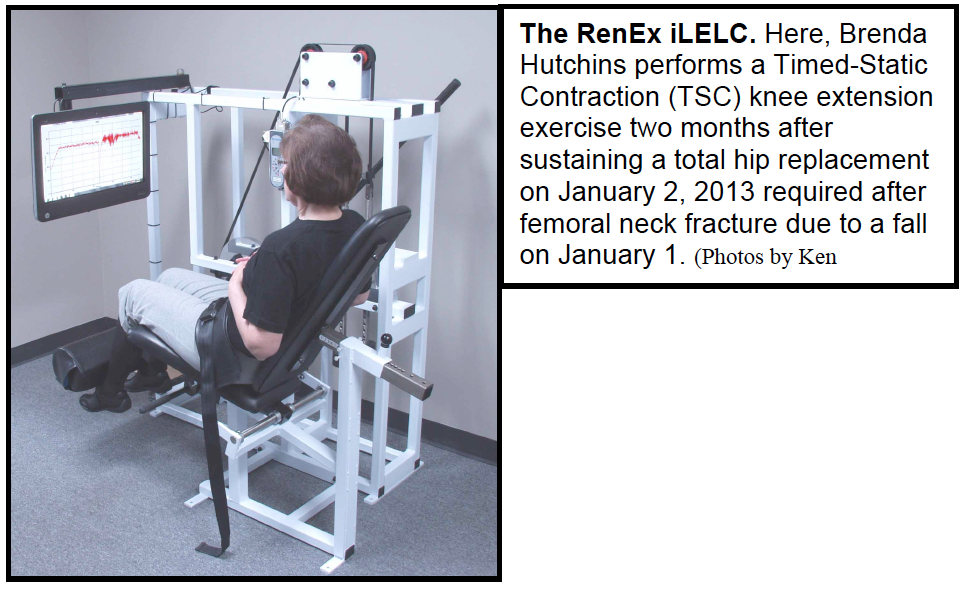

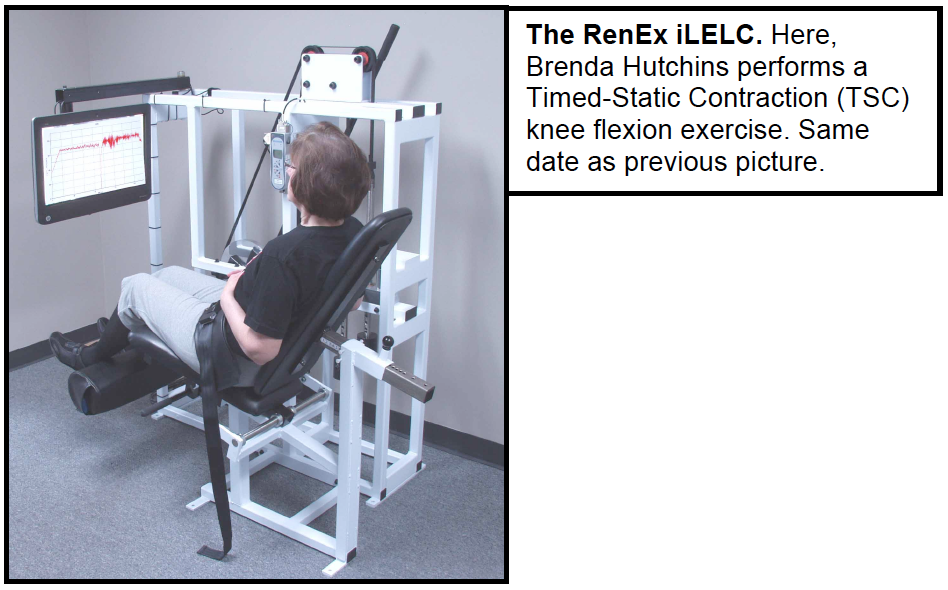

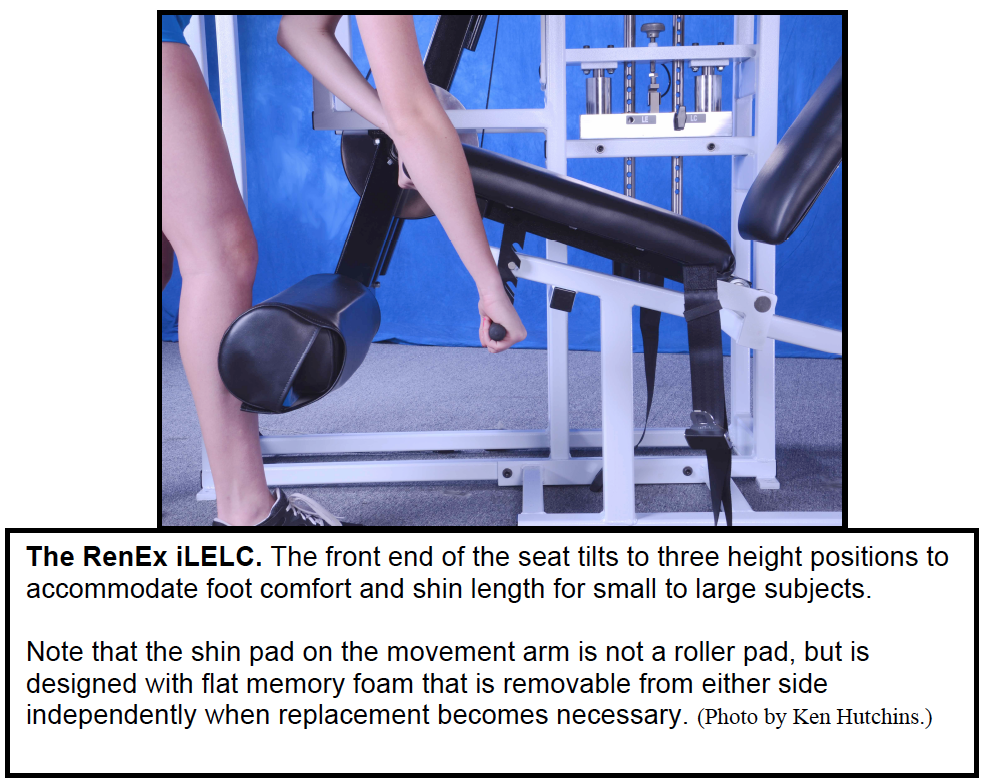

Meanwhile, our new static iLELC (Isometric Leg Extension/Leg Curl) addresses knee concerns that might allow for better control in certain rehab situations. The iLELC was first unveiled at the Future of Exercise Conference in Cleveland on October 6-7, 2012. The following pictures show many of its features.

If the static approach appeases the shear talkers, the new RenEx iLELC is made to order. For either knee flexion or extension, the knee musculatures can be deeply inroaded while keeping the knee in various mid-range positions to avoid extreme extension and/or painful positions. What’s more, TSC can be performed with exact force identification and recording of painful thresholds, if any, so that they can be avoided and tracked for abatement and improvement. This is what the physical therapy community has wanted and needed for decades—and now it’s here!

In addition, the long movement-arm handle, reminiscence of the dynamic SuperSlow System Leg Extension machine, has been retained for the convenience of joint lubrication.

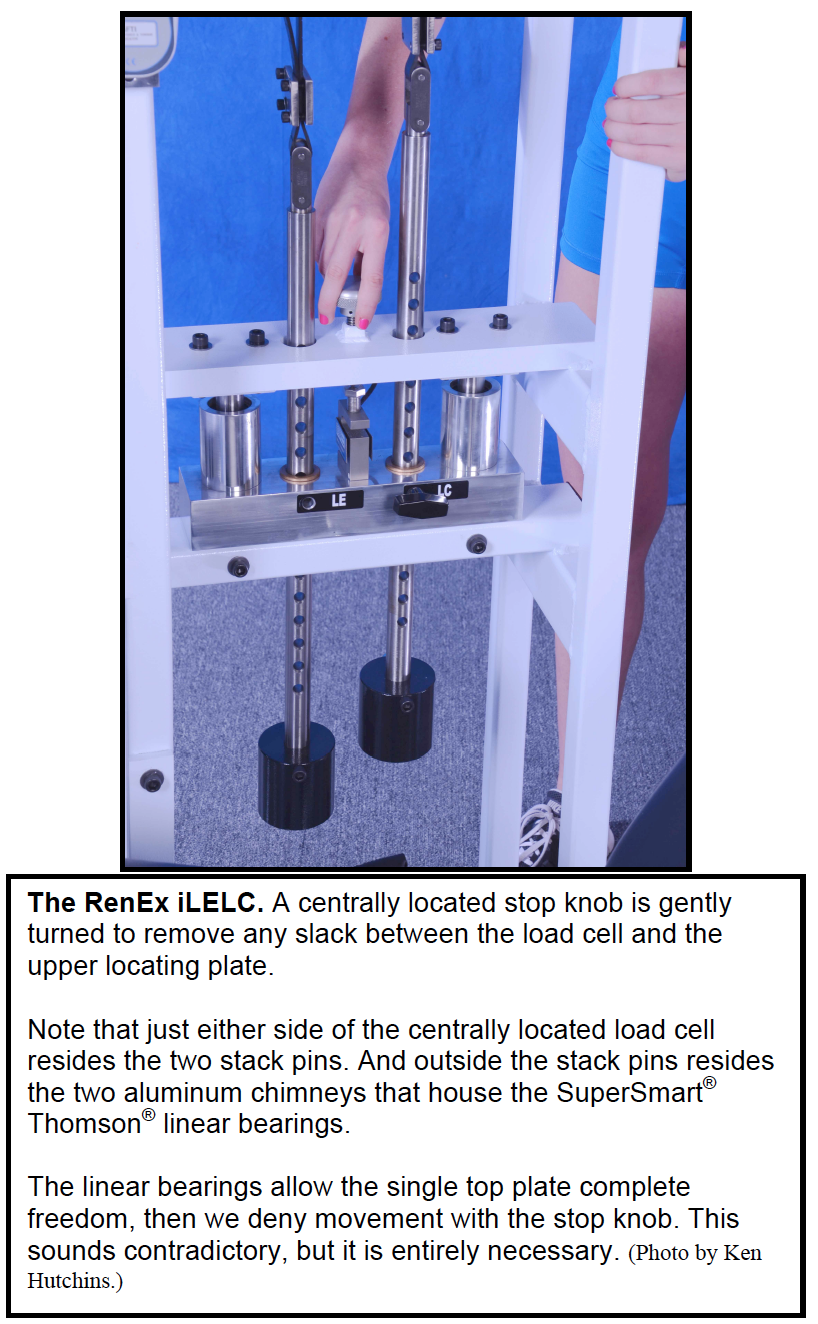

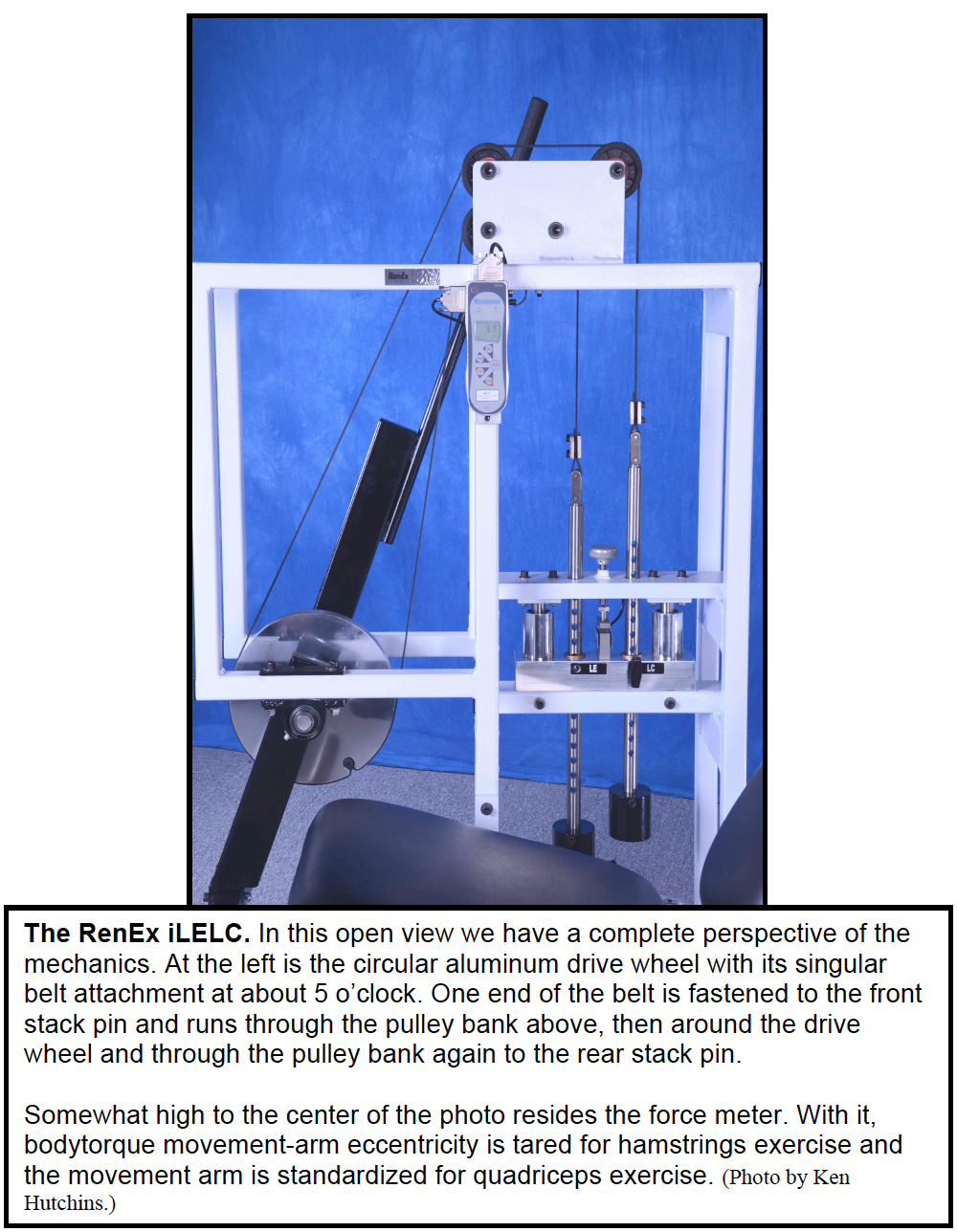

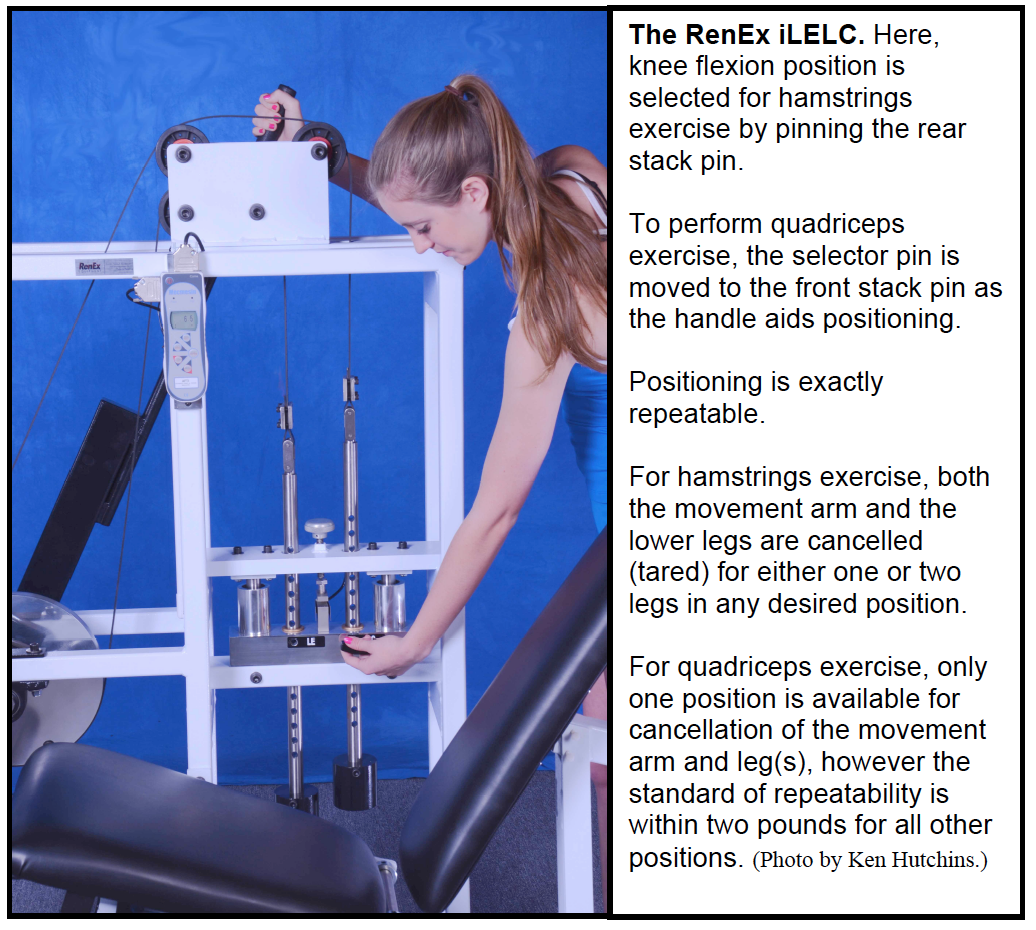

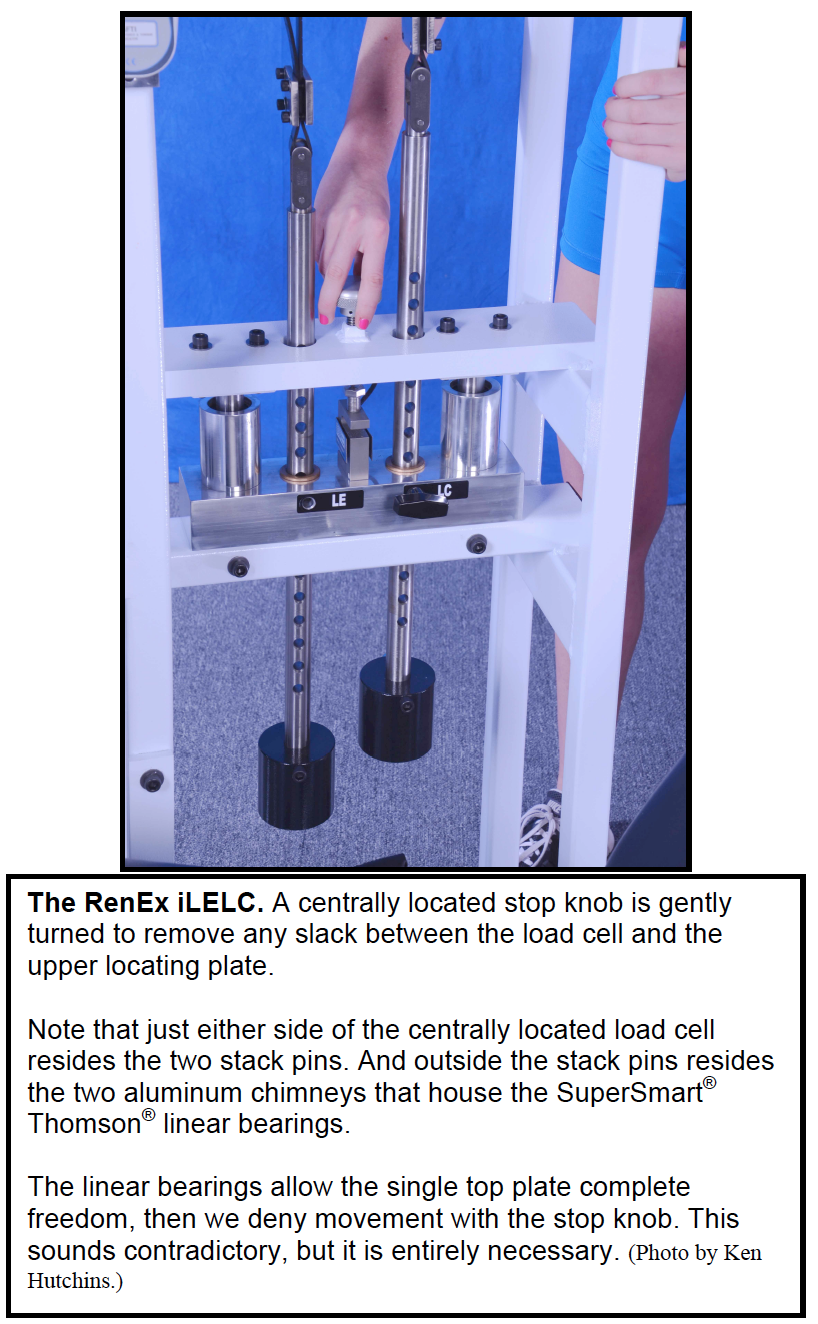

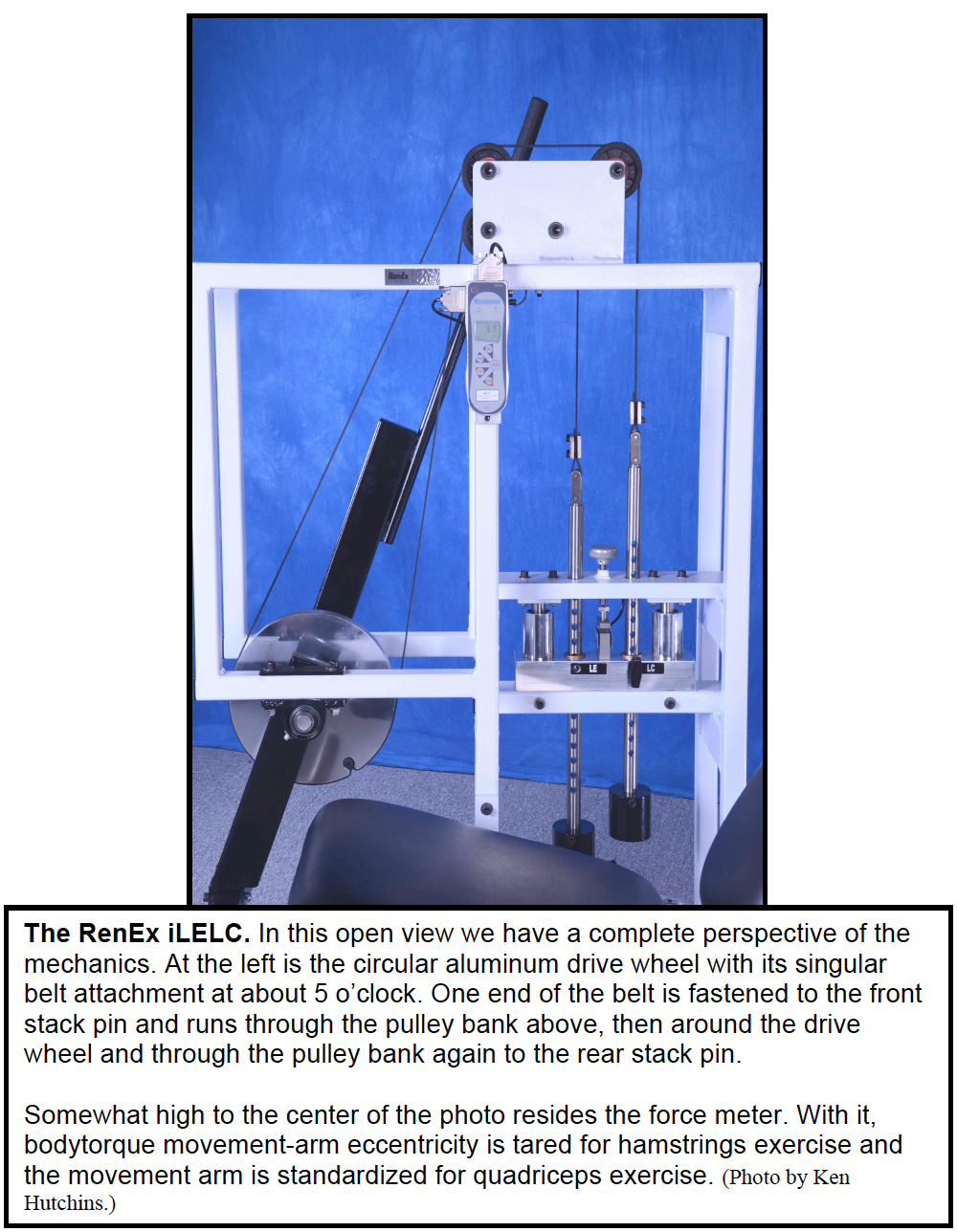

I designed the iLELC to operate with one movement arm that drives two stack pins in opposite directions using one continuous drive belt anchored in one drive wheel.

Either stack pin is engaged with a single top plate that compresses a single load cell.

With the application of TSC, we are able to dispense with some of the rigors of dynamic Leg Extension design. I hereby explain:

In the iLELC, the seatback is adjustable to accommodate the thigh length and buttocks depth in the usual fashion of most any knee extension machine.

However, the seat bottom is height adjustable on the front end to accommodate various lower leg lengths against the movement arm pad. This does affect knee/movement-arm alignment somewhat, but this is not a concern in a standardized static exercise.

The seat bottom adjustment also affects the hip angle, and would position taller subjects into muscular insuffiencies at full active knee extension, but this is no concern for performing mid-range TSC, the preferred positions for TSC.

And although dynamic knee flexion demands an abbreviated seat whereby the subject’s weight is primarily supported on the buttocks and not the hamstrings, TSC knee flexion exercise can utilize a seat that is the full length of the buttocks and thighs. This is possible because the TSC—again—is performed mid-range, and the distal thighs rise slightly from the seat as the lower legs are pulled against the movement arm. The hamstrings are, therefore, not compressed during the exercise on the iLELC.

The following photographs serve to augment my descriptions of this new and very effective device.

—Drum Roll and Herald Trumpets Please—

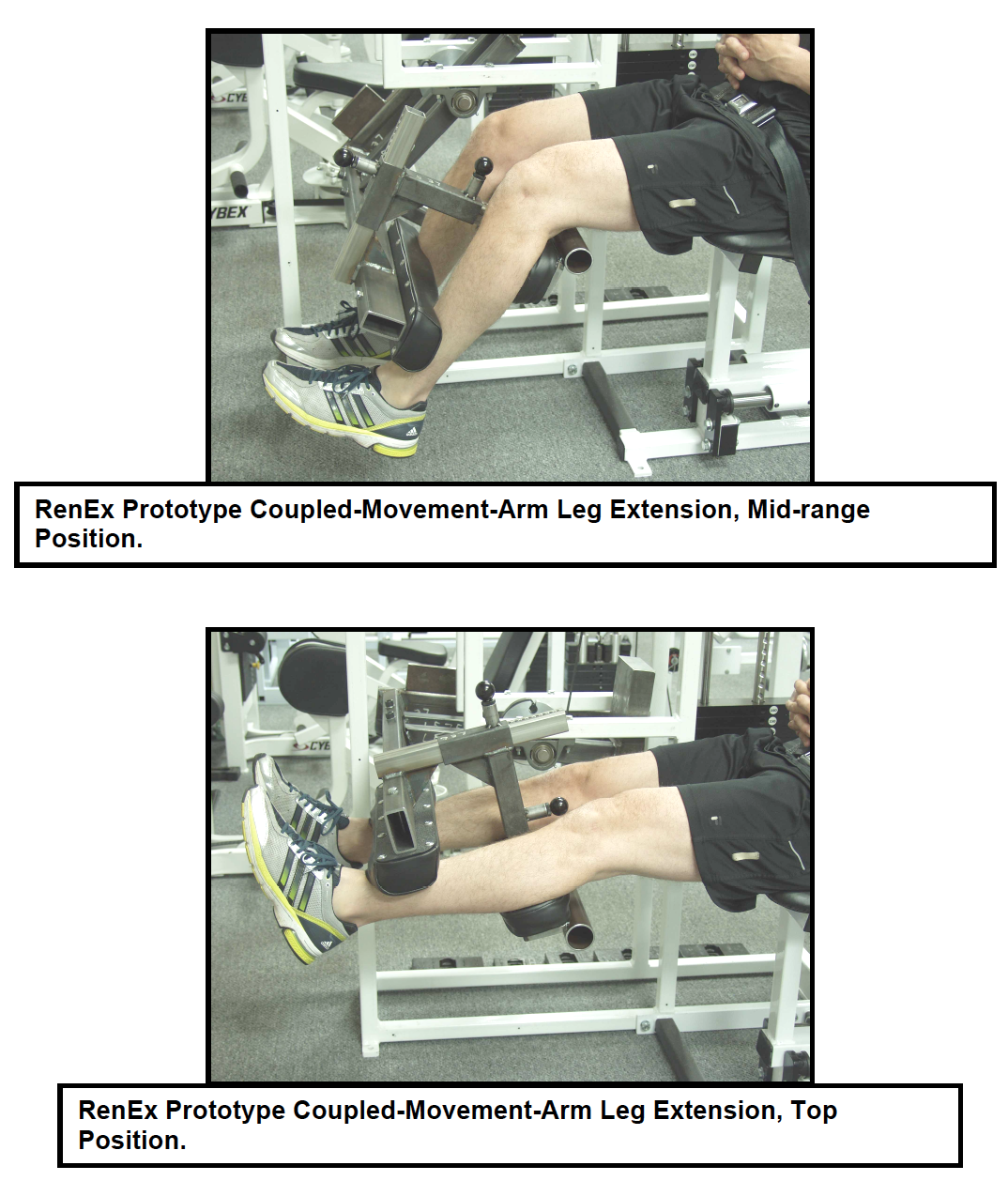

A Coupled Movement Arm for Knee Extension Exercise!

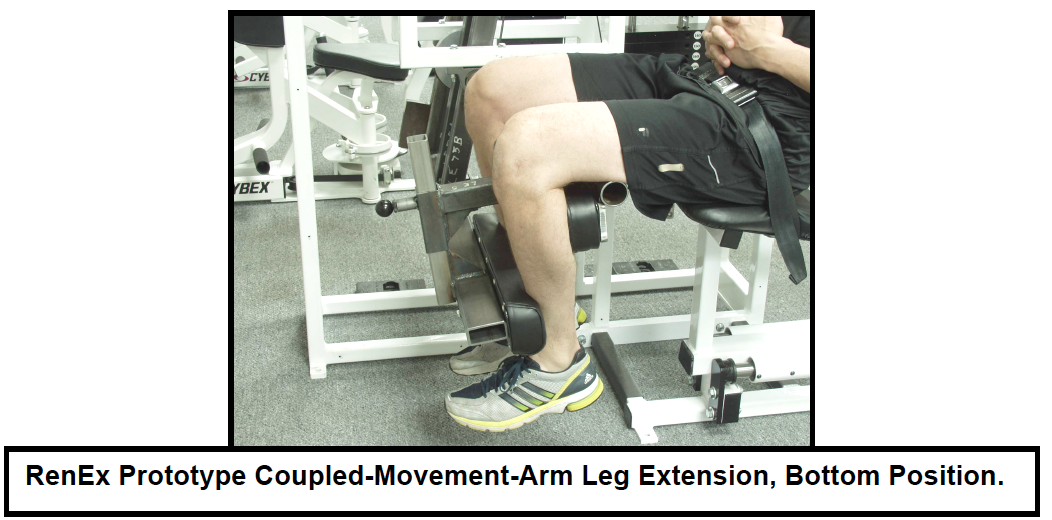

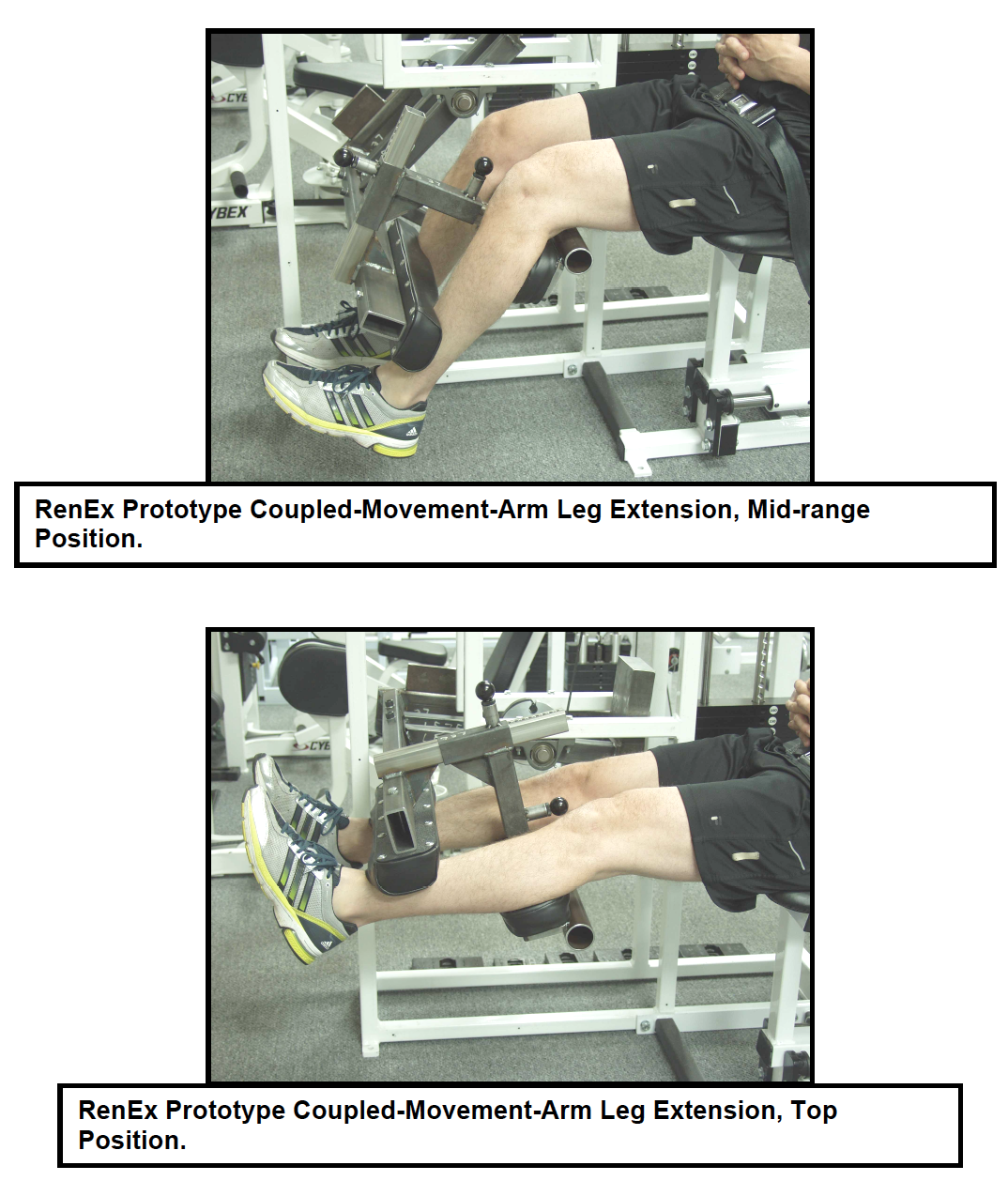

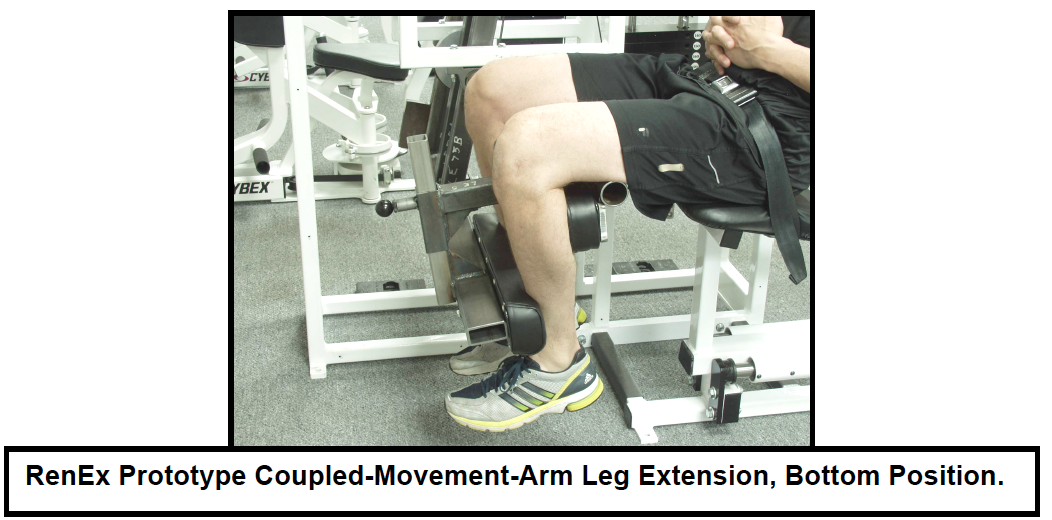

Just after completing Part III of this series (March 2013) I began to force the idea that I could build a coupled movement arm for a Leg Extension machine. My challenge was—not so much the issue of tolerance for the calf muscles—but the concern that the legs fall downward into the couple. I reasoned that I must admit the requirement to make adjustable stirrups for the feet.

The stirrups would certainly work, although I did not want to revert to horse-and-buggy technology. Then, on Tuesday, March 26, I saw the possibility of a dropout support for the thighs—a floor that supports the thighs (as well as the entire lower extremities like the front edge of a straight chair) during rest (entering or exiting the machine)—that rotates away and out from under the thighs as the movement arm is forced out of the starting position.

By April 1, 2013, I finished the prototype drawings and by Friday, April 5, 2013, my prototypists had it fabricated and installed on my vintage SuperSlow Systems Leg Extension machine. It works!

Then, we obtained photographic stills and videos and submitted it all for the patent process to begin. Provisionals have now been filed. So now I can share with you a few pictures, videos and reports.

We made two of these new movement arms with translating seats to install on our existing SuperSlow Systems Leg Extension machines in-house here and in Cleveland. They are being tested in these facilities to collect answers to the following questions and many more that we expect to arise:

- What is the best means to enter/exit this movement arm, and what do we need to improve this facility?

- Can it be applied to a wide or range of subjects, and are there specific conditions that need to avoid it?

- Do subjects with cruciate ligament concerns fare better with this movement arm than the typical—non-coupled—movement arm? (We believe that this answer is already at hand.)

- How are patellar/patellar-tendon concerns tolerated by this movement arm?

- How adjustable do we need to make this device?

- Do we desire to produce a Leg Extension machine with this device and also include a bodytorque counterweighting mechanism?

In the meantime, I used the new device twice as soon as it was installed and once again in mid-April. I had sustained some right patello-femoral trauma from using the Nautilus One Leg Extension back in 2009 and then more trauma to this site from jumping off the back of a delivery truck in 2011. Therefore, I was hesitant to try this device with a full load, especially since I considered this issue to be a patello-femoral problem.

Before attempting a light resistance (80 lbs), I thoroughly lubricated my knees using other available equipment. Then, to my surprise, I encountered no problems with the couple.

So I ramped the weight up to a moderate level (200 lbs—I regularly use 250 lbs on this device when my knees permit) and performed ten repetitions. Still, I encountered no problems, but I stopped there pending what my knees would report the following day. The next day I still had no problems.

I waited a couple of weeks and repeated my first experience. Afterwards, I did not do more until Josh Trentine arrived in May.

Joshua Trentine/Male/42-years old/Knee History by Josh Trentine

My first occurrence of knee issues began with anterior knee pain in 1984. It presented with inflammation and pain under the knee caps. It was diagnosed as “bilateral chondromalacia.” This condition was treated with strength exercise in a conventional physical therapy setting. I did get some relief, but anterior knee pain just became something I learned to live with from 1984 till 1990 when I began to have worse knee problems.

In 1990, I was badly injured while playing football. The injury occurred from an illegal chop block from behind. I ruptured my right anterior cruciate ligament, my medial collateral ligament, and had damage to my lateral collateral ligament as well as incurred a meniscus tear. Needless to say, my knee(s) have never been the same since.

The surgical reconstruction was a patellar tendon transfer. And when I am lean the heads of the anchoring screws are palpable and visibly outlined just under the skin on my proximal, medial tibia.

In my opinion, the methods for rehabbing the knee from the reconstruction were quite poor compared with the information I have now.

The knee surgery led to further complications which included right sacroiliac joint pain and the first signs of patello-femoral degenerative joint disease in my early 20s!

Needles to say, I’ve suffered with knee pain for most of my life by now. This condition has limited what activities and exercise I can do. Only with SuperSlow protocol was I able to resume intense and pain-free exercise.

The only other thing I could get away with was the occasional use of static contractions (TSC), but in the end both of these methods caused my knees to flare up so much that I decided to only do the SuperSlow Systems Leg Press thus avoiding the Leg Extension. This approach went on for a duration of about five years. Any other movement, of even different leg press machines, was bound to flare up my knees. Ken Hutchins’ SuperSlow Systems Leg Press became the tool and the method by which I could intensely train my lower extremities.

In 2011, Ken slightly decreased the range of motion on the SuperSlow Systems Leg Extension and made the fall-off faster although the total ratio of fall-off remained essentially the same. This difference was alluded to in Exercise for the Knee—Part III. I tried this and found it to allow my knee to perform heavy leg extension exercise for the first time in years. These changes were immediately installed in our machine in Cleveland as well as in the Leg Extension in Toronto.

Fast Forward to 2013: The new Coupled-Movement-Arm RenEx Leg Extension allows me to perform intense knee extension exercise pain-free and seems to really open up the knee joint. By this I mean that during the negative, the tibia seems to distract from the femur. I consider this to be a good attribute.

In 2013, I visited and used the prototype RenEx Coupled-Movement-Arm Leg Extension machine in the Florida RenEx lab three times. My first experience on the device was on May 24, 2013.

After some adjustments, I performed two sets. The second set was with the entire weight stack (350 lbs). As my knees have profound cruciate pathology and associated repairs, I was gratified to see that the couple allowed me to perform this second set to deep failure with five repetitions.

On July 20, I performed an entire workout with the prototype RenEx Coupled-Movement-Arm Leg Extension as the last exercise. I performed five repetitions again with 350 lbs and suffered no knee pain or limitation whatsoever. In fact, I had a feeling of enhanced knee security the following day.

I repeated this again with the same effect and outcome on November 24. The following link provides some video of my performance using this unique movement arm.

John Parr/Male/46-years old/Knee History by John Parr

Off and on from my late 20s to mid 40s, I have experienced knee pain and discomfort in one form or another: patellar tendonitis, stiffness, swelling, etc.

In the summer of 2007, my knee pain and swelling became severe enough to prevent me from strength training. I could barely walk or stand. Even sleeping was disrupted. After several months of suffering, in October of 2007, I decided to have surgery on my right knee.

At age 40, surgery revealed osteoarthritis. The surgeon said that he could not fix it and that I would be a candidate for a knee replacement in the future.

Then he said that the left knee looked worse than the operative (right) and, that although it was not yet symptomatic, it probably would be soon.

He was right. Six months later the left knee was worse than the right. I was devastated! How could this be? I always followed safe, sound, evidence-based, training advice. And, on the supposed finest equipment: Nautilus®, MedX®, and Hammer Strength®. My legs were my strongest, most well-developed body part, and I was proud of them. But I had to give up all leg training. I could not tolerate the pain.

Both of my knees are defective. There are dime-sized potholes opposite (underneath) my patellas that catch as I flex and extend my knees. This causes articular cartilage to be broken down with the deterioration of both my knee joints. Result: Inflammation and pain, as well as the need for doctor appointments to aspirate fluid with a huge syringe 3- 4 times a year. As the years passed my legs looked bad and atrophied.

Then, in 2009, I noticed a co-worker training hard, getting freakishly strong, and looking better every week by using the SuperSlow protocol.

I first met Ken Hutchins, the founder of the protocol, at his shop in 2003. I remember reading about his protocol in various books and articles over the years. And I knew it would be out of necessity that I use SuperSlow, now referred to as the RenEx Protocol, to try to resume training my legs effectively. Because of this man’s brilliant protocol, I could do a Leg Press without pain for the first time in years, and I got stronger. The rest is history.

In 2011, I went to the first-ever RenEx event where the new line of RenEx machines was unveiled. I became friends with Ken, Josh, Al, Gus, and the rest of the staff at Overload Fitness.

Fast forward to October 24, 2013: I was invited to visit Ken at his shop in Florida where a new prototype RenEx Coupled-Movement-Arm Leg Extension machine was being tested. I was anxious to try it.

Understanding the science behind how it was built, plus the fact that I have used probably over 25 different models from 15 or more different manufacturers of Leg Extension machines—all of them producing pain in my knees when I tried them—I expected this prototype to hurt my knees. I don’t know if it was because of the fantastic new coupled movement arm or the radical cam profile, but I did not feel any pain during or after performing the exercise precisely as directed.

As another benefit, you don’t need the use of the arms or hands on this version of the Leg Extension. You can just relax the hands and arms and really direct your effort on contracting your quads! You really stay seated in the machine!

This new machine feels like it is, and actually is, setting your knee into its proper alignment.

For days afterward, my knees felt great as I helped Ken clean up the back part of the shop by carrying heavy boxes up and down very steep stairs.

Great Job with the new machine guys! People like myself need it, and it’s the only one I feel safe enough on to put out a maximum effort as I go to failure in a set.

Conclusion

It seems we have a huge success with this movement arm. And as far as I know, this is a technology where no one else has gone before for the knee.

And many of our questions—already generalized—have formative answers. Yes, we have a way to go before we arrive at its ultimate development, but we are now well beyond the “Is-this-possible?” stage. And we are convinced that many knees require this device.

More generally, our success with the Coupled-Movement-Arm Leg Extension begs some historical questions:

- Why did Arthur Jones not already develop this? It was not easy for me to do, but it was not extremely difficult.

- Why did Arthur convince so many of his fans that the Leg Extension couple was impossible?

- Why do other self-professed biomechanics experts and prototypists among us declare that a Leg Extension couple is impossible—nuts to even try? Is this merely due to their blind respect for Arthur’s supposed omniscience on the subject?

- And is it really true that I am the only one to develop this approach? If so, why so? (Please inform me if others have succeeded.)

I am now in disbelief that these things are not already ubiquitous. Have all of us merely suppressed our own minds? Just ponder the thousands of physical therapists and orthopedic surgeons and equipment designers and biomechanical engineers and prosthesis companies and brace designers who have apparently overlooked this for the last several hundred years.

And might it be true that others did design this coupled movement arm, but then quickly abandoned it because it was impossible to safely control due to their application of excessive speed and unenlightened principles of cam effect?

Moving Forward

This concludes my series regarding exercise for the knee. I plan much more detail on this subject for the upcoming The Renaissance of Exercise—Volume II (ROE-2). With the exception that the RenEx Coupled-Movement-Arm Leg Extension is to continue development, I plan to focus entirely on the ROE-2. For now, I hope that this series has provided insight into a subject that demands serious discussion and application.

1. With extreme attention, build up force in a fashion gradual enough to barely break inertia.

1. With extreme attention, build up force in a fashion gradual enough to barely break inertia.