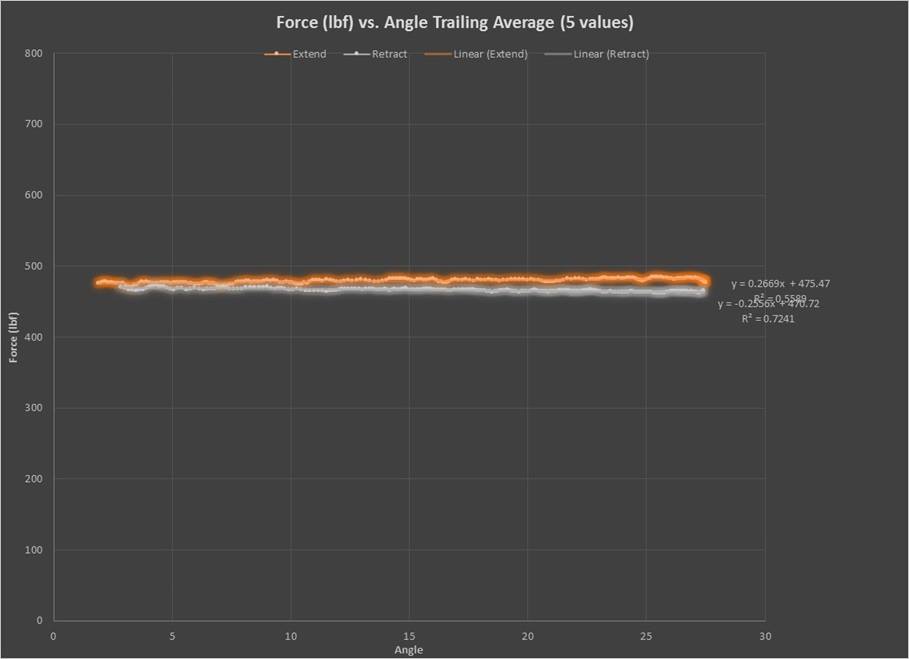

These are graphs of data that was collected for the MedX seated dip weight stack system early this year for friction measurement. Both graph the same data. One graph is zoomed in on the data. At the start of ROM the MedX seated dip stack has very low friction. At the end of ROM it peaks at a bit less than 2 percent. This was really the start of Project X. Project X will do this type of measurement while a person is training so we will know if the machine is functioning properly or not at all times. Unlike so many other force graphs out there these are by angle, not by time. The orange is the positive, the grey the negative. The difference between the orange line and grey line is the amount of force difference caused by friction.

ORIGINS OF PROJECT X

RenEx has a number of very high quality used pieces

we are going to sell, each week we’ll feature one.

And of course, as always, new RenEx is for sale too.

Retrofitted SuperSlow Systems Ventral Torso

This is an original SSS Ventral Torso that has been completely re-conditioned by Gus Diamantopoulos.

The weight stack features an Ultra-Glide top plate running on hardened matching guide rods and each of the bottom plates are fitted with premium virgin teflon inserts for nearly frictionless operation.

All fasteners, belts, and upholstery has been replaced and the machine performs with butter-like smoothness.

$4,500

Contact Gus: workout@thestrengthroom.com.

Serious inquiries only please.

The Flying Kangaroo Lands Me at Overload

by Pete Collins

It started with a visit to the Renaissance of Exercise website, the articles were thought provoking, precise and professional, free of pop culture, gimmicks, ego & spin. My curiosity grew to a somewhat moderate level, I purchased Ken’s The Renaissance of Exercise Vol 1, my interest grew to somewhat more of a moderate level, I enrolled to study Level 1 certification, upon studying the material and viewing the videos my interest ramped up to a maximal hard as I dare passion for the principles outlined and practiced by the team at RenEx & Overload Fitness.

It started with a visit to the Renaissance of Exercise website, the articles were thought provoking, precise and professional, free of pop culture, gimmicks, ego & spin. My curiosity grew to a somewhat moderate level, I purchased Ken’s The Renaissance of Exercise Vol 1, my interest grew to somewhat more of a moderate level, I enrolled to study Level 1 certification, upon studying the material and viewing the videos my interest ramped up to a maximal hard as I dare passion for the principles outlined and practiced by the team at RenEx & Overload Fitness.

It was an easy decision to invest in the cost of the study material, the book, the FOE DVD’s, flights from Melbourne Australia and hotel fees in Beachwood Ohio because I felt fully confident that the knowledge I would access on this trip would be well worth the investment.

Travis, an articulate, well presented and pleasant young man kindly picked me up from my hotel to visit Overload and meet the team. When I entered the reception I was struck by the warmth & welcoming environment, clean, well-organized, professional and appealing, I recall thinking, this is exactly the welcome a perhaps nervous potential client needs to diffuse any sense of held negative ideas about visiting an exercise facility. No sweaty bodybuilders and scantily clad gym junkies hanging around reception chewing protein bars and sucking on shakes to frighten off the clients here, “I like this”, I thought.

Separated from the reception & exercise area at the back are the offices of Josh Trentine and the team of dedicated instructors. I was introduced first to Al Coleman, a sharp, professional, well-mannered guy but with an unassuming coolness and easy going nature beneath that sharp focus. Al immediately surrendered his own priories and time to chat with me, show me around the exercise area, discuss the various machines and provide some insight into the philosophy of Overload, right from the start I was learning, taking mental notes ready to log later on, conversationally Al was putting many of the fragmented pieces I have previously learned together in my mind, there were many “Ah! Ha!” moments. I was introduced to Kristina, Deidra & Jessie, after being greeted with warm smiles I could see this team was busy, planning, taking care of follow ups, running the business and focusing on their client experience.

I was introduced to Josh Trentine, a busy guy, on the go, I immediately felt his passion for this business, the way he talked, the discussions with the other team members, sharing in knowledge. He is a focused guy who congruently lives and breathes his passion, he is a straight down the line talker, no jibber jabber or idle talk, he got straight to the point but I was struck with his opening conversation with me. “Pete, keep a log, have a think about what you want from this and tell me because I want to ensure your time and trip all the way here is the best experience you can have for yourself” I felt grateful and honored to be treated in this manner, this is philosophy of Overload towards their clients and one of the key aspects that separates these professionals from the rest.

To be honest, I tried to hide it from the guys but I was seriously jet lagged and suffering from breaking my normal eating routine and environment but really wanted to get on the machines. Although I did not complete a full designed workout, the experience was phenomenal. Josh instructed me through a set of Leg Press with feedback, immediately my previous experiences of gradual loading on the Kieser MedX leg press was pulled apart, with visual feedback you can literally see if you are skipping gears as you build force breaking the weight stack on the first repetition. The visual feedback gives you instant and usable information allowing you to very quickly correct discrepancies, this would normally take much time and practice between instructor & subject, adding to the subjects learning costs in paid fees and making the instructors time inefficient, this tool alone adds value for the client and maximizes margins for the business.

To be honest, I tried to hide it from the guys but I was seriously jet lagged and suffering from breaking my normal eating routine and environment but really wanted to get on the machines. Although I did not complete a full designed workout, the experience was phenomenal. Josh instructed me through a set of Leg Press with feedback, immediately my previous experiences of gradual loading on the Kieser MedX leg press was pulled apart, with visual feedback you can literally see if you are skipping gears as you build force breaking the weight stack on the first repetition. The visual feedback gives you instant and usable information allowing you to very quickly correct discrepancies, this would normally take much time and practice between instructor & subject, adding to the subjects learning costs in paid fees and making the instructors time inefficient, this tool alone adds value for the client and maximizes margins for the business.

Next Josh instructed me on the ICRo, immediately I violated every rule in the protocol, Val Salva, bracing, not relaxing the jaw & white knuckle gripping the handles, understandably Josh was not impressed, he firmly but politely stated this to me and clearly explained to me how to correct these violations, again as with Leg Press, the visual feedback provided me the information along with Josh’s clear instruction to quickly improve all aspects of my form. Clear, assertive and precise instruction is critical, no yelling, berating of championing here, just quality instruction with one goal, safely and efficiently inroading the musculature.

Next Josh instructed me on the ICRo, immediately I violated every rule in the protocol, Val Salva, bracing, not relaxing the jaw & white knuckle gripping the handles, understandably Josh was not impressed, he firmly but politely stated this to me and clearly explained to me how to correct these violations, again as with Leg Press, the visual feedback provided me the information along with Josh’s clear instruction to quickly improve all aspects of my form. Clear, assertive and precise instruction is critical, no yelling, berating of championing here, just quality instruction with one goal, safely and efficiently inroading the musculature.

Next Josh instructed me on the OHP using Project X. At first I overwhelmed myself and again violated many safety principles, quickly, clearly and assertively again Josh corrected my ways, explaining what & why, after a very disappointing first set, I was able to use the visual feedback to rapidly improve and correct my form during the next practice set, this second set was incredible, following the rep procedure striving to achieve a perfect score I was blown away how quickly the resistance overtakes your strength, strength rapidly goes down while simultaneously effort ramps up, like two polar opposites travelling at equal speed.

Project X will redefine and set new standards for businesses between instructor & client, the target parameters are not open to subjective guesswork or opinion, recording of the workout is precise thus giving the instructor the data to decide how to grade performance and when to increase resistance, this means for the client accurate recording of performance, very accurate setting of meaningful resistance to ensure maximum inroading and stimulus of the growth mechanism during every workout , again this makes the instructor more efficient reducing cost slippage to the business and maximizing value for the clients investment that can be accurately and tangibly experienced by way of measuring progress.

Project X will redefine and set new standards for businesses between instructor & client, the target parameters are not open to subjective guesswork or opinion, recording of the workout is precise thus giving the instructor the data to decide how to grade performance and when to increase resistance, this means for the client accurate recording of performance, very accurate setting of meaningful resistance to ensure maximum inroading and stimulus of the growth mechanism during every workout , again this makes the instructor more efficient reducing cost slippage to the business and maximizing value for the clients investment that can be accurately and tangibly experienced by way of measuring progress.

Small but critical tips provided by clear instruction are vital, Josh & Al instructing me introduced me to an whole new level of what an instructor is, the cues and simple one word prompts literally make or break the quality of the exercise, proper coupling, correct placement, using the ‘5 Analytical Stages of Alignment’ and gripping of handles, body attitude, using the seat belts and entering machines correctly are vital and it is absolutely necessary that in order to safely perform exercises with maximum efficiency you have to be instructed by a RenEx instructor. I have never been in the hands of such an expert as these guys before and miss this. If you are going to invest in an instructor, you must consider a RenEx certified instructor.

As for the RenEx machines themselves I would like to share my experience. **Note I am certain that had I had more time, several weeks on a learning stages generic routine in order to proficiently learn how to precisely perform each exercise, accurately record, qualify and set adequate settings & resistances I would be able to write for you now a very detailed article about the differences between RenEx machines and all others that make this equipment superior.

However this is what I can say confidently. The leg press provided a direct, linear and super smooth experience in both the positive and negative parts of the repetition, the weight Josh selected although accurate was irrelevant to me, I did not even know what he selected, the seat felt right, locking my hips and gluteus musculature in a position that allowed for very intense engagement of all of the lower body and frontal thigh muscles, upper and lower turnarounds can be performed very precisely as there are no sticking points or friction, the upper and lower stack come together and break very precisely, the inroading experience felt much more direct and rapid than my past experiences on other machines.

Both the OHP & VT machines tracked muscle and joint function in a much more natural way for me, using the seat belts during these movements intensified the loading upon the intended musculature in a way I have never experienced, allowing me to drive hard, intensely contracting the musculature powerfully whilst at all times preserving musculature around the spine & neck.

The Pull Down machine seemed to perfectly track my strength curve, until you use a RenEx machine with a timing crank you will never experience appropriate cam fall off in the way I did, but don’t be fooled, even though the resistance falls off at muscular contraction, performing a squeeze technique in this position is insanely difficult, there is no escape, ensuring tension throughout the full range of movement delivers unbelievable fatigue.

The same applies to the CRo machine, the sliding seat and pushing with the chest against the pad in a true linear fashion with those unbelievably smooth bearings is an entirely superior experience to the MedX compound row, again even with cam fall off, the squeeze technique was incredibly demanding to perform, With Al’s precise instruction to correct elbow position the overall effect was amplified, again RenEx instructors give you nowhere to hide but the payoff for being disciplined is that you maximize the value of your workout.

The workout area itself is quiet, cool & appropriately lit, it is organized and machines are appropriately positioned together to minimize time between exercises, this was clearly evident when I was invited by Al Coleman to watch him perform his A routine, for example moving between biceps machine pull-down & triceps machine to Ventral Torso, by the way, if you want inspiration on how to go from a relaxed state to instantly flick the switch from the moment to his body touched the pad and seat delivering an insane laser focused all-out effort, you need to watch Al train in person, this guy’s attention to detail and flawless execution of each repetition to failure is a sight to behold and a standard which to aspire to.

I watched the unbelievably strong Josh Trentine workout proving RenEx machines deliver a brutal effect and level of intensity in preparation for his bodybuilding contest,I watched Travis skillfully instruct his fellow colleague and instructor Candice through her workout, It is the first time I have witnessed a woman exercise so hard and efficiently inroad her strength levels, Candice’s turnarounds, focus on effort and performance of repetitions was a lesson to me in itself and testament to the entire ethic & philosophy of everybody involved in RenEx and Overload. I am grateful to have been welcomed by each and every member of the team, the knowledge I acquired in just 1 week is both exciting and priceless, the knowledge provided by Overload can be directly and immediately applied to your own workouts to improve your strength, health and mind in ways I have never seen another business provide. Your health safety, happiness and strength are your responsibility in your hands, but equally you will be in the best hands in the world to accomplish your goals, dreams and desires by investing your time and hard earned money with RenEx & Overload Fitness.

I have made friends for life and I will always be part of this family because I truly believe all of the hard work, dedication, passion, resilience and life blood of these guys will be rewarded with success and reward all who embrace the Renaissance of Exercise.

Thank you

Pete

HVT? | A Forum Topic in The Inner Circle

Not a member of the RenEx Inner Circle and curious as to what’s going on in there?

There are some seriously awesome conversations going on. Here’s one example of a topic currently being discussed over on the forum right now!

———————————————————————————-

HVT?

by Joshua Trentine | Administrator

I’ve been competing in natural bodybuilding for over 20 years now on every level imaginable, over this period of time I have been able to interview 100’s of very good bodybuilders. My primary conclusion : I don’t know how they do it….1 to 2 hours a day, 5 to 7 days a week…sometimes 2x/day doing strength exercise, then they do 30 min to 3 hours of steady state in a day and then there is the MASSIVE amount of food prep time. Oh ya….as the show draws near practice of the mandatory poses and creating an artistic night show routine.

I’ve been competing in natural bodybuilding for over 20 years now on every level imaginable, over this period of time I have been able to interview 100’s of very good bodybuilders. My primary conclusion : I don’t know how they do it….1 to 2 hours a day, 5 to 7 days a week…sometimes 2x/day doing strength exercise, then they do 30 min to 3 hours of steady state in a day and then there is the MASSIVE amount of food prep time. Oh ya….as the show draws near practice of the mandatory poses and creating an artistic night show routine.

To me this looks like a full-time job w/ no pay….what is left for family, friends, fun and business????

To me this looks like a full-time job w/ no pay….what is left for family, friends, fun and business????

It’s really a massive commitment and I respect it, I just don’t know if the juice would be worth the squeeze for me, but in the end I’m a hacker (words of Tim Ferris) and I’ve always wanted to get the result, but worker smart rather than long.

Guess what? while the actual scheduled time commitment for me may be 1/3 as much as orthodox bodybuilders it still mounts up and still forces me to adjust my thinking and my schedule all day, everyday. The neat thing is that the structure can actually improve my productivity rather than take from it, as the above schedule for the conventional bodybuilder is just too consuming and certainly not sustainable….we’ll for me at least….and I don’t even have any commitments outside of RenEx. I never got how guys with a full-time job and family can pull it off. I’d like to share the commitments that I’m putting into this project, in the end maybe it’s HVT ?

So…for this contest I use RenEx exclusively. I train 2x/ week and every week….one of the workouts can be as many as 10 exercises, mostly single joint on that day. That workout could take 25…maybe even 30 minutes. The other one is briefer and mostly compound exercises. It is usually done in 20 min. Not so bad so far, but wait….it does mount up as the show draws near.

For me a good carb load is an essential part of looking my best on show day, so as the show draws near I begin to practice my “carb-up”. These require me to reduce my carb intake for a few days….do some activity to help dump as much glycogen as possible then really push the carbohydrate for a couple days…usually practiced on weekends.

Next as the show draws near the mandatory poses must be practiced at least a few days per week, which is absolutely grueling and mine as well be full-body high-intensity workout sessions….towards the end these poses must be done daily.

Next…the lost art….preparing a choreographed night show routine….this can take months to prepare. Funny, most skimp on this part , but to me a “professional bodybuilder” must be that in every aspect…..modern judging criteria has really allowed for this slip in night show standard. This choreography is also time consuming and exhausting….and note this is all done in a calorie deprivation which might eventually be 1500 calories (or so) less than you would like to take in.

Now of course we have food preparations, which for me are minimal…I need no slow-cooker, no microwave, oven or stove….just a good pair of kitchen/meat scissors. I would say the time that I save on food prep and strength exercise is what allows me to participate in the sport…my commitment for the week may be equivalent to what a number of guys have to spend in one day on training and food prep….but I’m not sure a lot of people are willing to do it the way I do though….there is always a give and take and to do it this way every second, of every inch, of every rep, of every exercise, and time between must be accounted for, optimized, and laser focused in your training and for me my eating paradigm completely flipped…it’s no joke 🙂

Now of course we have food preparations, which for me are minimal…I need no slow-cooker, no microwave, oven or stove….just a good pair of kitchen/meat scissors. I would say the time that I save on food prep and strength exercise is what allows me to participate in the sport…my commitment for the week may be equivalent to what a number of guys have to spend in one day on training and food prep….but I’m not sure a lot of people are willing to do it the way I do though….there is always a give and take and to do it this way every second, of every inch, of every rep, of every exercise, and time between must be accounted for, optimized, and laser focused in your training and for me my eating paradigm completely flipped…it’s no joke 🙂

Then there are sleep requirements….my goal every night is to be in bed by 9:30 or 10pm, at the latest, so I can be up a 4am to tend to business and the extra requirements mentioned above. So in the end it “feels” like high-volume to me…and maybe it is ? but my hat is off to my competitors….they are all extraordinary for the time they commit.

For those of you who don’t “like” the bodybuilding talk on here…lol, and this may include Ken Hutchins….bare with me…I’m knee deep in this until December and it’s what’s on my mind right now. We’ll provide plenty of other content in the modules every month and we have much more to share this month that we are still working on….I suspect the overall content of this site will go way up when I can get these bodybuilding commitment behind me.

For those of you who don’t “like” the bodybuilding talk on here…lol, and this may include Ken Hutchins….bare with me…I’m knee deep in this until December and it’s what’s on my mind right now. We’ll provide plenty of other content in the modules every month and we have much more to share this month that we are still working on….I suspect the overall content of this site will go way up when I can get these bodybuilding commitment behind me.

Curious…i know a few of you who follow the forum have competed…what are your thoughts and experience?

The content of this post is, in my opinion, just a very good description/expression of what it takes to…..well whatever one wants to accomplish. And also a good reminder of how we should proceed with exercise. Focused to make every second count so to reap the most benefits in the least time.

I never stood onstage but I’m fairly deep into exercise too if that means how many hours a day I’m occupied with it.

At forehand,all the best for the event.

ad

Dr. Doug McGuff | featured

Joshua,

Joshua,

I think you should discuss your prep much more than you are doing here. This is a once in a lifetime opportunity for us to have insight into contest prep using RenEx principles. There are many out there who think it cannot be done.

Get Jeff or Al to video each workout between now and contest day and post it. Give us some video documentation of your food prep and eating. Give us a “day in the life” video experience.

I only competed once as a teenager in the 1980’s. Made the cut to the night show and placed 4th. I was the only one in the night show who was not using Deca, Anavar or both. I mistimed my peak and looked my best two days after the show (after a pizza binge), so I can see the value of the carb load.

I only competed once as a teenager in the 1980’s. Made the cut to the night show and placed 4th. I was the only one in the night show who was not using Deca, Anavar or both. I mistimed my peak and looked my best two days after the show (after a pizza binge), so I can see the value of the carb load.

The hardest part was stopping. I developed so much momentum heading into the show, that once it was over it was hard to ratchet back on training and diet. When I did let my leanness return to baseline, it was somewhat depressing.

Anyway, I think we can learn the most about protocol way out at the margins. This is a learning opportunity that should be documented here to the maximum extent possible.

Chime in folks. Let Josh know. We want more.

Pete Collins | featured

Doug, I agree and I cannot improve upon what you said there, so I second you. Go for it Josh, make our day, this would be excellent.

Doug, I agree and I cannot improve upon what you said there, so I second you. Go for it Josh, make our day, this would be excellent.

Pete

I agree with Doug too (of course!!). I mean this is the INNER CIRCLE of renex. so share this preparation with its members. And a sneak preview would be appreciated too:(.

Thanks ,

ad

Joe A | veteran

Success in any endeavor requires a high volume approach toward its achievement. The problem is, many people spend way too much time doing things that matter very little and very little time doing things that could make all the difference. Preferences and natural abilities tend to guide behavior here. This is opposite of the way highly successful individuals operate, at least the ones I’ve seen.

Success in any endeavor requires a high volume approach toward its achievement. The problem is, many people spend way too much time doing things that matter very little and very little time doing things that could make all the difference. Preferences and natural abilities tend to guide behavior here. This is opposite of the way highly successful individuals operate, at least the ones I’ve seen.

So, when you say, “I’ve always wanted to get the result, but work smart rather than long,” this is somewhat misleading. Statements like this may be attractive to the lazy (like HIT began to attract), but this is not a good thing. That is not the way your approach should be marketed, as simply an option for people who do not have the time or discipline to invest in themselves more than a few minutes each week.

The fact is, while your time spent exercising may only be a few minutes each week, your investment toward the achievement of your goal is massive. You’ve simply identified where time is best spent and allocated your efforts to accommodate it. Consider the time it takes to conceive and build machines/technology that actually allow for just minutes of exercise. Consider the time experimenting with food to optimize the timing of your appearance. Consider the time it takes to perfect your posing. Consider the time spent educating yourself (reading, experimenting, consulting with experts, possibly traveling to them) toward the optimization of all of the variables that lead to the achievement of your end goal. This isn’t even an exhaustive itemization of what you’ve invested.

The fact is, while your time spent exercising may only be a few minutes each week, your investment toward the achievement of your goal is massive. You’ve simply identified where time is best spent and allocated your efforts to accommodate it. Consider the time it takes to conceive and build machines/technology that actually allow for just minutes of exercise. Consider the time experimenting with food to optimize the timing of your appearance. Consider the time it takes to perfect your posing. Consider the time spent educating yourself (reading, experimenting, consulting with experts, possibly traveling to them) toward the optimization of all of the variables that lead to the achievement of your end goal. This isn’t even an exhaustive itemization of what you’ve invested.

Yours is not a minimalistic approach by any measure. Quite the opposite, actually.

This will be true for your consumers too.

A diabetic subject attempting to control their condition may only spend minutes of their week renting your equipment and instruction, but the actualization of their goal will require much more; optimizing the allocation of their effort, energy and time. It is a daily, sometimes hourly grind toward success.

Doug wants to be a successful author or ER physician; time must be allocated according to what is required. I don’t view him as a minimalistic exerciser, but rather a high volume live-er. Nothing about him hints of an unwillingness to go to great lengths for results, despite <1 hour/week in a gym.

We tend to have an exercise-centric perspective when we discuss goals, results, etc. Back up and look at things more holistically. If the goal is health, the investment will be large, with time for exercise appropriately allocated. If the goal is competitive, the investment will be large, with time for exercise appropriately allocated. If the goal is appearance, the investment will be large, with time for exercise appropriately allocated.

Successful people don’t go into their endeavor with the mindset of, “what’s the least amount of time/effort I can put into this and still make some money?” This is a slippery slope to tread down. I, personally, hate the “least amount necessary” mindset, simply because of where I’ve seen it lead.

Whatever your goal, expect a hefty expenditure of time and effort in the journey toward it. The goal should be to optimize one’s efforts in the necessary categories and allocate your time accordingly. Success requires a HVT approach, regardless of how much time you spend under load…

Joshua Trentine | Administrator

Joe,

Joe,

I can’t disagree with anything you say here. The basis for my exercise selection is that which works best for me….end of story. The point of my post was to express how much time and effort this bodybuilding thing takes and to include that if I had to do it the orthodox way I would likely fail to sustain… or perhaps fail to attempt.

I also agree that RenEx is anything but minimalistic…..

To clarify, my post was in agreement with your original post. My point was that, performing a relatively minimal amount of exercise is not the same as being minimalistic toward achieving a goal. Achievement of goals require one to lean toward OCD more than minimalism.

The trick is where/how you spend your time and energy…optimizing your efforts, instead of spinning your wheels.

More people fail at bodybuilding than succeed using orthodox methods. I think it is due to poor allocation of the time and energy they are clearly willing to put into their goal.

More people fail at bodybuilding than succeed using “HIT-type” methods. I think it is due to a misunderstanding of how much it takes to achieve this goal (not how much exercise, but how much it takes, period).

Your post gives some insight as to how much one must invest. Most people who seek minimalistic are not going to invest that much…which is different than your obvious willingness to go to great lengths and arriving at a somewhat minimal application, or rather optimizing the conditions to create a somewhat minimal application of the exercise component…leaving time for all of the other components which are as (or more) important toward the end goal.

rambling…

———————————————————————-

Interested??

Check out what an Inner Circle

membership entails at www.renexinnercircle.com.

HIT: Acronym Acrimony

HIT: Acronym Acrimony

By Joe Anderson

High-Intensity Training (HIT) is an inadequate moniker for the concept of exercise and needs to be decommissioned. Additionally, the HIT ‘community’ has all but stalled toward the advancement of exercise and dissociation seems prudent. I’ll admit I’m probably not the one who should be writing this. Further, it is unfortunate, albeit obvious, that such lines must be drawn.

However, if the goal is to advance exercise, then I submit that those advancing it must be willing to make the necessary distinctions in order to sufficiently distinguish exercise from ALL other activities (including and especially those which are similar and related). I believe the RenEx associates have done this well, the lingering HIT association notwithstanding. It is time to part ways.

This may seem disrespectful to those who have forged the path that we continue to travail, but I assure you it is not. We honor their contributions by advancing beyond them. In my opinion, it is disrespectful to simply enjoy the fruit of their labor, content with “if it was good enough for them, then it is good enough for me.”

This reminds me of a poem entitled The Bridge Builder by Will Allen Dromgoole. An old man decides to build a bridge across a formidable chasm he proved crossable. He took the time to build the bridge so that those following after him, possibly less capable than he, could similarly cross it.

This reminds me of a poem entitled The Bridge Builder by Will Allen Dromgoole. An old man decides to build a bridge across a formidable chasm he proved crossable. He took the time to build the bridge so that those following after him, possibly less capable than he, could similarly cross it.

You can read the entirety of this piece here.

While I’m sure some will disagree with the nature of this old man’s intention, the point remains: a bridge was built. Some may approach the bridge and simply stand in awe of it. Others may cross the bridge just to try it out, with no desire to travel beyond. Still others may decide to find alternative ways to cross the same chasm or improve upon the design of the bridge. Yet others, upon crossing the bridge built for them, travel onward, charting new territory.

I believe the associates of RenEx are the latter. It is time to move forward.

High-Intensity Training (HIT)

There is not a clear description of HIT, at least not one that I’m aware of, which makes this critique challenging. To better understand HIT, it seems appropriate to start with its inception.

Dr. Ellington Darden was the first to describe a method of exercise as High-Intensity Training, coining the HIT acronym. HIT was in reference to Arthur Jones’ vision for proper exercise: a preference for a progressive application of “outright hard work” performed for the entire body, which necessitated a relatively low volume of exercises and frequency of performance (as compared to the bodybuilding ‘norm’ of the 1970s)…and rest.

- Outright hard work

- Full-body routines

- Relatively low volume of exercises

- Relatively low frequency of performance

- Progression

- Rest

That was perhaps the clearest explanation of HIT there has ever been. It seems that from this point forward, HIT has been used to describe dozens of different (and often conflicting) ‘methods’ of strength exercise. A genesis of unfortunate word choices spawned an ambiguous concept, which has been bastardized as needed to the liking of whoever chooses.

There is no greater impediment to the advancement of knowledge than the ambiguity of words.

—Thomas Reid

Does the phrase “high-intensity training” improve or impede understanding of what is attempting to be described?

Consider the term “intensity,” which means the degree, volume or magnitude of a thing.

Presumably, intensity is in reference to the concept of “outright hard work”; the degree, volume or magnitude of the effort involved. The descriptor “high” is then added to further convey the concept. “High-intensity” is suggested to mean a full effort; exhausting one’s ability to perform (i.e. training until muscular failure).

Given enough background and context, the use of this phrase to express to-failure training becomes more comprehensible. However, the phrase “high-intensity” already has an established meaning in exercise science literature. In reference to resistance training, intensity is a percentage of one repetition maximum (1RM). Typically, high intensity is expressed as >80% of 1RM. [Note: scientific literature often uses the phrase “resistance training.” It too is a worthless descriptor of the exercise activity, but I digress.]

In a recent paper, James Fisher et al. discussed intensity as “the percentage of momentary muscular effort being exerted” and suggested other authors follow suit. I applaud their effort, however in the meantime high-intensity is widely accepted as meaning a heavy load. Such ambiguity is unnecessary since we have the ability to simply refrain from using this term or choose a more precise one.

“Training” was another poorly chosen word by Dr. Darden. The term has a sports or performance connotation, commonly used as the preparation necessary to acquire the skill or proficiency for an event. This is understandable, in that HIT was born out of the bodybuilding culture, where athletes were preparing for competition.

However, with the conversation moving toward exercise as a means to improve health and function, this lingering connotation is undesirable. Exercise is not training; performance is not the point; competition is not the goal. (Tangentially, the term “Trainer” is not an appropriate way to identify a person who instructs exercise; neither is “Coach”. Circus elephants have trainers; sports teams have coaches; exercising subjects simply need an “Instructor”).

However, with the conversation moving toward exercise as a means to improve health and function, this lingering connotation is undesirable. Exercise is not training; performance is not the point; competition is not the goal. (Tangentially, the term “Trainer” is not an appropriate way to identify a person who instructs exercise; neither is “Coach”. Circus elephants have trainers; sports teams have coaches; exercising subjects simply need an “Instructor”).

Further, the use of “training” is counterproductive toward developing the mindset and corresponding behavior appropriate for exercise. Not surprisingly, this training mentality is common in HIT and errant terminology is culpable.

High-Intensity Training does not describe exercise in a meaningful way. Rather the phrase is ambiguous and an impediment toward advancement. It is an obstruction in communicating, understanding and developing the appropriate mindset for exercise. It is time to remove it from our vocabulary.

An error is the more dangerous in proportion to the degree of truth which it contains.

—Henri-FrédéricAmiel

The problems with HIT extend beyond semantic inferences and are firmly rooted in the philosophical foundation. There are two specific trains of thought that seem to have derailed HIT:

- Train for muscular strength in order to build muscular size

- Exercise for increasing strength should be brief, infrequent, and intense

Strength Training

“The strength of muscle is in direct proportion to its size.” Arthur Jones took that statement and noted the following:

- To increase the strength of a muscle, you MUST increase its size.

- Increasing the size of a muscle WILL increase its strength.

- If all of the other factors are known and allowed for, then an accurate measurement of the size of a muscle will clearly and accurately indicate the strength of the muscle —and vice versa.

- There IS a DEFINITE relationship between muscular strength and muscular size.

Once the above points are clearly understood, the implications are obvious;

a) bodybuilders, who are primarily interested in muscular size (with or without actual muscular strength) MUST train for maximum-possible muscular strength in order to build maximum-possible muscular size

b) weightlifters, who are interested only in strength, MUST train for maximum-possible muscular size in order to build maximum-possible strength (Size or Strength, The Arthur Jones Collection)

This line of reasoning led him to the following conclusion regarding exercise performance:

“You should perform as many repetitions as momentarily possible without sacrificing good form. Do not stop at 10 repetitions merely because that is the upper limit of your guide figures, continue for as many repetitions as possible…12, 15, or whatever number you can perform in good form…if you can reach or exceed your guide figure, then that is a signal to increase the resistance; the fact that you can perform more repetitions than you anticipated is proof that your muscles have grown, so you are stronger, and need more resistance.” (The Relationship of Muscular Mass to Strength, ArthurJonesExercise.com)

In the absence of the ability to control enough variables and thereby standardize exercise performance, I’m not sure what, if anything, can be deduced from the event. “In good form” is insufficient for any meaningful comparison to be made.

I am sure that exercise performance improvement is not evidence of muscle mass increase. It is neither a sign of progression, nor is it a sign to progress. When “strength” is measured by exercise performance and the goal is simply to improve it…baddabing, badda boom- the assumed objective of exercise.

HIT seems to promote the belief that “doing more than last time” is both the stimulus for adaptation and the signal that adaptation occurred. This line of thought promotes the need to “get more reps” in order to “add more weight.”

It has always seemed odd to me that HIT prided itself on working harder, not longer; yet the intent of each exercise was an attempt to do more. The measure of “progress” unfortunately becomes a sign that a subject figured out how to work longer, not harder. This intent and the resulting behaviors are exactly opposite those of proper exercise, yet they are rampant within HIT.

This is not to say that progressive loading is problematic or to be avoided. Rather, progressive loading needs to be distinguished from progression. Whereas progressive loading is a decision, progression is an adaptation; it is a consequence of a stimulus. The decision to progress loads in order to increase exercise demands should not be done haphazardly, nor is it the only means to increasing exercise demands.

Brief, Infrequent and Intense

Arthur Jones correctly observed the relationship between effort, volume and frequency of exercise; that these variables influence one another. For productive exercise, he viewed effort as paramount, which was a shift from the volume-dominated thinking of the times. If effort were great, the resulting volume and frequency would not be. HIT exercises were performed to failure (his view of 100% intensity), with much less volume and repeated much less often than the bodybuilding norm. “Brief, infrequent and intense” became the HIT mantra.

Somewhere along the line, “brief, infrequent and intense” ceased being an acknowledgement of the influence effort has on volume and frequency and became an aspiration unto itself. What was once a consequence was now a cause. The variables became ends unto themselves, as if the point were the brevity, the infrequency or intensity. A person can develop the ability to effectively exercise themselves in a brief, infrequent and intense application. However, you can’t simply decide to work out infrequently or decide to work out briefly, simply because you worked to “failure” on your sets. An oversimplification of the exercise variables basically degraded Arthur’s astute observation into a peculiar HIT logic:

High intensity = train to failure

Muscular failure = weight won’t move anymore

Hard work will be brief = only perform one set

Fully Recover = come back next week

Progressing = added a rep (or TUL) OR moved more weight

Not Progressing = genetic limitation

“Brief, infrequent and intense” is a description of productive exercise, not the prescription for it. Without any real means of discerning the influence and affect these variables have on a subject, I’m not even sure a relevant prescription is possible. Yet, with exercise performance improvement (lifting proficiency) as the judge and jury of progress, HIT seems to embark on a journey toward ever diminishing volume and frequency, trying to evade the overtraining boogeyman as “intensity” (load) rises.

This HIT Logic has led some on the quest for super-intensity, ultra-brief and extremely infrequent exercise. I find it humorous that attempts at “least amount necessary” have mostly produced “least effective possible.” Trying to force these variables into being only leads to the behaviors that prevent the activity from actually necessitating them!

There is no need to manufacture a brief, infrequent and intense scenario; proper exercise most certainly will become relatively intense, brief and infrequent as the exercising subject hones in the ability to inroad himself, as adaptation improves the level of output, as lifestyle influences recovery (nutrition, stress, sleep, etc.), and, most importantly, within the constraints of the paradigm one is exercising. And, if you find yourself in need of a tagline for exercise, I would suggest, “safe, effective and efficient.”

A subtle thought that is in error may yet give rise to fruitful inquiry that can establish truths of great value.

– Isaac Asimov

HIT was a step in the right direction at one point in time. However, the advancement of exercise requires a divergent path.![]()

The missteps of HIT provided the quandary that has given rise to more fruitful inquiry. Exercise will only advance to the degree we are willing to relinquish these errors (despite any sentimental attachment) and discover where the current inquiry leads. It is time to put aside anything obstructing our objective, including HIT associations that prevent it from being taken seriously as a method of exercise.

Let’s move exercise forward without pandering to a Bodybuilding audience, without the baggage of the Paleo and Low Carb communities, without mentioning Ayn Rand.

The renaissance continues…

RenEx Experience

RenEx Experience

Joe Anderson

8/30/13 Workout at OVERLOAD Fitness

• Leg Press TSC

• OHP (with Project X feedback)

• Compound Row TSC

• Simple Row

• Ventral Torso

• iPO

• iPD

The Beachwood OVERLOAD facility has changed A LOT since last I was there…and so had my exercise expression (still got a ways to go). I’ve commented previously on how bad I was the first time there (and Josh will confirm…all I gotta say is Ventral Torso…oh, boy…smh). I do believe the initial experience, as well as my “keen observation” of the RenEx materials (online, printed, audio, etc) helped with improvement. However, this pales in comparison to the impact of RenEx solutions in the studio today.

I had previously exercised on prototypes, but the equipment I experienced today had been updated and further refined. I cannot overstate the detail that has been put into making the end user’s experience simple, repeatable and productive. Further, the feedback is a game-changer. I had briefly experienced feedback on the iPOPD at a RenEx workshop…but today I got to experience the full effect of its impact on the learning process…and the inroad process – WOW!

The experience with Project X was awesome (gotta say that like Bowfinger). Such a cool idea…and really could be the ‘thing’ that takes this to a whole new level, as the ‘guys’ ideas for further features come to fruition. It must be gratifying to see one’s vision become reality. I commend the entire Team for DOING the work it has taken to make it happen. If there was doubt previously about the commitment of this Team to advance exercise (and there wasn’t), it would have been removed today. I have seen the product of their relentless efforts…I have seen the future of exercise, and it is bright as hell!!

Big thanks to Josh, Al, Ken, Gus, Jeff…and Jeffrey Muehl.

More Than a Gym…More Than a Workout!

Dear Overload:

Thanks for a great experience this past Tuesday July 30, 2013.

To call your facility a “gym” and to call my experience a “workout” does not begin to do justice to what went on. Even though I have used Nautilus since 1972, MedX on and off over the past 10 or so years and a slow training protocol with John Tatore since late winter, I was surprised and delighted with Tuesday’s collaborative effort.

In business, you generally need some equipment, some systems, and some people to run the systems. If one of those elements is weak, the business can fall apart. Overload is just outstanding in all three areas. Josh did a great job guesstimating my needs and strength levels from John’s charts. Josh also delivers training with a great balance of discipline, humor, knowledge, compassion, appropriate feedback, and ability to adjust machine settings even in the middle of a set. In particular, his instruction and comments on the Simple Row machine were spot on given my profession (dentistry) and my slumped-over posture. That the equipment is unbelievable goes without saying.

In business, you generally need some equipment, some systems, and some people to run the systems. If one of those elements is weak, the business can fall apart. Overload is just outstanding in all three areas. Josh did a great job guesstimating my needs and strength levels from John’s charts. Josh also delivers training with a great balance of discipline, humor, knowledge, compassion, appropriate feedback, and ability to adjust machine settings even in the middle of a set. In particular, his instruction and comments on the Simple Row machine were spot on given my profession (dentistry) and my slumped-over posture. That the equipment is unbelievable goes without saying.

If you are looking for a typical gym experience, join a typical gym. If you want to get strong in the most time-efficient manner possible and use absolute state-of-the-art equipment coached by people who know what they are doing and care about you, check out Overload.

Sincerely,

Peter Michaelson, DMD

Windsor, CT

Conversations on the RenEx Inner Circle Today!

We are having some very stimulating conversations over on the RenEx Inner Circle! Here are some examples of what’s going on just TODAY!

Owen Drolet has replied to a forum topic

Topic Title: TSC with feedback as future of exercise

Daniel wrote,

“Your question “why wouldn’t TSC w/feedback be superior?” is still largely unanswered. I have a few ideas bouncing around, but I think this topic requires its own thread to properly flush everything out.”

Whether on this thread or a new one I think it would make a fascinating discussion. I’d be curious to hear anyone’s educated thoughts/theories even if all the data isn’t in yet.

I am very excited about TSC’s potential as a teaching tool, which is why I am getting the iPOPD. I know what just one session did for me and I had already spent years considering the underlying concepts, etc.. I’m fascinated to see what multiple sessions does for the worst performing of my clients, especially given that the dynamic work they do will still be on largely conventional equipment. I know it will improve their performance, by how much is what I’m looking forward to witnessing.

————————————————————-

Joe Anderson has replied to a forum topic

Topic Title: TSC with feedback as future of exercise

@Owen

Beyond the benefit of its efficacy as a teaching tool, the major implication is rehabilitation and working around debilities/limitation/contraindications. Even if the potential of TSC is less than the dynamic counterpart, that fact can be thrown out the window if a person is unable to perform the dynamic option safely, or pain free.

My intrigue with TSC is not the possibility of stand alone potential, but rather, the possibility of adding simple exercises (to a routine dominated by dynamic compound movements), without the added wear/tear. Most simple exercises involve musculature that are involved in the compounds, SO, if there is added benefit to dynamic work, it may still be achieved? I also wonder if it may be better to address simple exercises where the musculature that crosses multiple joints via TSC…eliminates the need to address the challenges of the full ROM with wicked cams, while trying to maintain a singular body position that is safe through the ROM.

Specifically, I’m thinking of LE, LC, biceps, forearms…curious if TSC may just be a better option period. I suspect that some of the more delicate musculature/joints (like the neck) are best addressed with TSC…and I suspect the musculature of the shoulder may benefit from TSC, given how involved the shoulder girdle already is in just about every upper body movements. If one needs to address the musculature around the shoulder specifically, it would seem TSC would be advantageous when trying to minimize wear/tear.

————————————————————–

I was having a conversation today with another exercise instructor. He made mention of the idea out there in internet world that a prevailing thought among “personal trainers(HIT specifically)” is that clients pay us so they don’t have to think otherwise they wouldn’t need our service.

Myself and the other instructor I was talking to both believe this is total BS and this particular thought or view of our subjects is a serious symptom that can, and will, dictate how a instructor will ultimately treat his clients.

The more deeply one THINKS and considers the factors and potential response, the more they come to appreciate the need for the environment, instruction, equipment, feedback…”The Service”.

Long term clients will have to, at some point, view this type of strength exercise as a discipline (like martial arts)…in order to buy in fully to their role.

Instructors cannot, and should not, treat their clients like dummies who just need a coach to push them….this will NOT lead to long term retention or instructor or client satisfaction.

Thoughts from the group?????

If you’re not a member yet, go here to join the conversation!

Yet Another RenEx Experience

July 19, 2013 at 2:38 pm

Mike L says:

Good afternoon to all, Earlier this week my family and I decided to take a trip from Western NY to Sandusky, Ohio for a vacation to Cedar Point. On the way there I made a stop in Beachwood, Ohio for a initial workout consultation at Overload Fitness. I was given a tour of the facility and was instantly impressed with all the equipment. I noticed right away the temperature was very comfortable in the exercise room at around 62-65 degrees. After a couple minutes a man about 6 feet tall and about 225 lbs, most of it muscle, greeted me. His name is Josh Trentine. Josh spent about 1 hour with me informing me on the proper way to exercise including workout form, cadence speed, frequency of workout and explaining to me the benefits of strength training. My goal for this appointment was to learn how a 51 year old man can improve his muscle function and be fit as humanly possible without injury.

After listening to Josh’s advise for an hour it was time for me and my chicken legs to got through an Overload workout. Josh first introduced me to the computerized shoulder press. The goal is to push the weight slowly and keep up with the lines on the graph. I struggled the first 3 times as it is a learning curve to begin with. After the 4th try I did it pretty decent and was very impressed at how smooth the machines are. The amazing thing is when you are trying to keep up with the tracing it seems to go much faster than you think at about 20 seconds. Josh did not take me till failure on this one but I can tell you even short of failure I felt it.

Next was to the leg press machine which we went close to failure and it was enough to make these skinny legs shake.

The next machine was a static pulldown machine that was also computerized. The goal of this machine was to slowly exert force to certain line on the computer then maintain it and allow your muscles to fail. This machine was awesome but really hard as I knew my heart rate was going up pretty high.

The next machine was a static pulldown machine that was also computerized. The goal of this machine was to slowly exert force to certain line on the computer then maintain it and allow your muscles to fail. This machine was awesome but really hard as I knew my heart rate was going up pretty high.

The last machine was the static leg extension which worked the same as the pulldown machine and once again was awesome and tough.

It was a very good experience for me and wish there was a facility close to me in Western NY. One thing I liked is that Josh would keep me on track and motivate me. I now believe that anyone can reach their true potential if they were to train at a facility like Overload Fitness.

——————————————————————————————-

If you don’t have access to a RenEx licensed facility you can still benefit tremendously by learning first hand and in real time the techniques and innovations we use everyday at OVERLOAD Fitness by joining the RenEx Inner Circle. Click here to join TODAY!